Pillar 10 — Pitch Delivery

Section 1 — The Moment Investors Stop Listening to Your Slides and Start Judging You

At some point in every pitch, investors stop engaging with your slides as content and start reading them as a proxy for you.

Most founders never realize when this happens.

They assume investors are still “understanding the idea,” still open, still neutral. But in reality, the shift happens early—often before the founder thinks the pitch has even begun.

This section of the deck is where that shift becomes decisive.

By now, the investor has already seen the basics:

what you’re building

who it’s for

why it exists

Those questions are largely settled. The investor’s attention moves elsewhere—to something far less explicit and far more consequential:

your judgment.

Investors do not back ideas.

They back decision-makers operating under uncertainty.

From this point forward, your deck is no longer evaluated as information—it’s evaluated as evidence of how you think.

This is where many founders unknowingly hurt themselves.

They keep explaining fundamentals.

They keep adding context.

They keep justifying assumptions that don’t require justification.

To an investor, this feels like insecurity masquerading as thoroughness.

What they hear isn’t:

“This founder is thoughtful.”

What they feel is:

“This founder might not know what really matters.”

Experienced investors are extremely sensitive to over-articulation. It suggests the founder hasn’t yet developed an internal hierarchy of importance.

Great founders do the opposite.

They don’t try to show everything they know.

They show they know what to ignore.

That restraint is not stylistic. It’s strategic.

From the investor’s chair, restraint implies:

confidence in first-order drivers

comfort with ambiguity

ability to prioritize under pressure

discipline in decision-making

These traits matter more than elegance, polish, or performance.

This is also where many “beautiful” decks fail.

A deck can be visually perfect and still raise red flags if the thinking feels soft, reactive, or scattered. Investors would rather see imperfect slides backed by coherent judgment than flawless design hiding shallow reasoning.

At this moment in the pitch, investors are implicitly asking:

Would I trust this person with $5M?

How will they decide when the data is incomplete?

Can they distinguish signal from noise?

Will they overreact—or underreact—when something breaks?

None of those questions are answered directly.

They are answered through structure, focus, and what you choose not to say.

This is why this pillar matters. It exists to help founders understand that decks are not persuasive documents—they are diagnostic instruments. Investors aren’t looking for explanations; they’re looking for proof of maturity.

And maturity shows up long before the closing slide.

At this stage of a pitch, investors are no longer reacting to slides — they’re evaluating the founder’s decision-making quality. This is also where many founders realize that ad-hoc preparation, slide tweaking, or expensive pitch consultants rarely fix the real problem. What actually helps is having a single, coherent system that forces clarity across the pitch deck, sales narrative, and financial logic — so delivery reflects real judgment, not performance. That’s why some founders replace fragmented prep with a VC-ready pitch system that aligns thinking, structure, and delivery from the ground up.

Section 2 — What Investors Are Really Evaluating at This Stage

Once investors cross from understanding into judgment, the criteria change completely.

They are no longer asking, “Is this interesting?”

They are asking, “Is this fundable?”

The difference is subtle—but critical.

Fundability isn’t about ideas, markets, or even traction in isolation. It’s about whether the founder demonstrates an integrated understanding of how all these elements interact.

This is where many founders misdiagnose rejection.

They assume investors didn’t understand the product. Or didn’t like the market. Or wanted more traction.

In reality, investors often reject because the deck revealed how the founder reasons when complexity increases.

At this stage, investors scan for five things:

Hierarchy of importance

Do you clearly signal what matters most versus what’s just supportive information?Causal reasoning

Can you explain why outcomes happen—not just that they happen?Trade-off awareness

Do you acknowledge constraints, risks, and choices without defensiveness?Consistency of logic

Do claims on one slide reinforce—or quietly contradict—claims elsewhere?Decision framing

Do you make it easy for an investor to imagine saying “yes” with conviction?

Weak decks collapse these dimensions into noise. Everything is emphasized equally. That’s dangerous.

When everything feels important, nothing feels decisive.

Strong decks feel selective.

The founder appears to be saying:

“These are the three forces that matter. Everything else is downstream.”

That clarity is magnetic.

Experienced investors intuitively trust founders who can compress reality into understandable systems. They assume—correctly—that those founders will be capable of navigating future uncertainty.

This is why you’ll often hear VCs say:

“The founder really gets it.”

“They have strong judgment.”

“They think clearly about the business.”

Those phrases don’t refer to intelligence.

They refer to decision quality under ambiguity.

And ambiguity is the constant state of startups.

When this part of the deck succeeds, investors stop questioning whether you understand the business and start questioning whether they want exposure to it.

That shift is the beginning of momentum.

What often gets misunderstood here is that investors are not scoring answers — they’re recognizing patterns. These patterns come from repetition across hundreds of pitches and are rooted in how investors process risk, ambiguity, and founder behavior — something explored more deeply when breaking down how investor psychology shapes funding decisions.

→ investor psychology

Section 3 — Why Investors Trust Structure More Than Story

Founders often believe that if they tell a compelling enough story, investors will fill in the gaps.

In reality, investors do the opposite.

They trust structure first — and only then allow the story to work.

This is because investors have learned, often the hard way, that stories are cheap. A confident founder with strong verbal skills can make almost any opportunity sound exciting for thirty minutes. What separates a fundable founder from a persuasive one is whether the story survives structural scrutiny.

Structure answers questions before they’re asked.

When investors scan this part of the deck, they are subconsciously checking for:

logical sequencing

cause-and-effect relationships

consistency across slides

alignment between claims and evidence

restraint in what’s highlighted

These signals tell them whether your story is grounded in reality or floating above it.

Weak decks rely on narrative momentum. They hope enthusiasm carries the room. Strong decks rely on architecture. Even if the investor stops paying attention to your words, the logic still holds together.

This is why experienced VCs often say things like:

“The deck told a clear story even before the founder explained it.”

What they really mean is:

“The structure itself made sense.”

Founders who misunderstand this try to “save” weak structure with better storytelling—more context, more passion, more explanation. But to an investor, this signals the opposite of confidence.

Structure is a credibility shortcut.

When your deck is well-structured, investors assume:

you’ve thought deeply about trade-offs

you understand dependency chains

you know which dynamics come first

you can prioritize under uncertainty

These are CEO-level traits. Investors are not just backing an idea—they’re backing someone who will make hundreds of high-impact decisions with imperfect information.

This is also where many first-time founders fall into a trap: they optimize for persuasion instead of decision support. Investors are not asking you to convince them. They are asking you to help them decide.

Structure does that quietly, efficiently, and without hype.

Once investors trust the structure, the story no longer feels like a pitch. It feels like an explanation of how the market actually works—and where this company fits inside it.

That’s the point where belief becomes possible.

Investors don’t trust stories because they’ve seen too many collapse under pressure. What they trust is structure that continues to make sense when retold, questioned, or summarized internally. That’s why slide sequencing and logical frameworks matter far more than narrative flair — they create consistency investors can rely on even when the founder isn’t in the room.

→ slide structure and frameworks

Section 4 — Cognitive Load: How Investors Decide in the First 3–5 Minutes

Founders often underestimate how little cognitive bandwidth investors actually allocate to a pitch.

Not because they don’t care — but because decision-making at scale forces efficiency.

A typical VC might:

skim 30–50 decks per week

take 5–10 first meetings

juggle portfolio issues in parallel

prepare for IC discussions

manage partner dynamics

This means one thing:

Your deck is not competing against other decks.

It’s competing against investor fatigue.

By the time an investor reaches this section, their brain is already filtering aggressively. They are prioritizing signals that help them answer one question quickly:

“Is this worth deeper attention?”

This is where cognitive load matters more than almost anything else.

Cognitive load refers to the mental effort required to process information. High cognitive load causes hesitation. Low cognitive load creates flow.

Weak decks accidentally increase cognitive load by:

introducing too many concepts at once

forcing investors to remember unrelated facts

jumping between ideas without clear hierarchy

mixing vision, execution, and data on the same slide

requiring verbal explanation for basic logic

From an investor’s perspective, this feels like work.

Strong decks do the opposite. They reduce cognitive strain by sequencing ideas the way the brain naturally processes information:

one dominant idea per slide

supporting evidence that directly reinforces that idea

clear transitions that feel inevitable, not abrupt

consistent framing across sections

repetition of core logic without redundancy

This is why experienced investors often describe good decks as “easy to follow.”

What they really mean is:

“I didn’t have to fight my brain to understand this.”

And when the brain doesn’t encounter resistance, confidence increases.

This is also why pacing matters so much. Pacing is not about speed — it’s about mental recovery.

Strong founders intuitively create micro-pauses:

a slide that clarifies before introducing complexity

a simple visual before dense information

a summary moment before a strategic leap

These pauses give the investor’s brain time to lock in understanding before moving forward.

When cognitive load is managed well, investors stop worrying about comprehension and start exploring implications:

“If this works, what happens next?”

“How big could this get?”

“Where does this break?”

“What would capital unlock here?”

Those are investment thoughts.

If, however, the investor is still trying to understand what you just said, those deeper questions never surface.

Great founders design their decks not to impress — but to protect investor attention.

And when attention is protected, belief has space to form.

Cognitive overload doesn’t come from complexity alone — it comes from poor visual hierarchy and pacing that force investors to work too hard. Design decisions quietly shape how ideas are processed, which is why founders who understand design as a decision-support tool — not decoration — communicate more effectively under pressure.

→ pitch deck design principles

Section 5 — Why Flow Matters More Than Individual Slides

Most founders obsess over individual slides.

They ask:

“Is this slide good enough?”

“Does this slide explain the point clearly?”

“Should I add one more data point here?”

Investors don’t experience decks that way.

They don’t remember slides individually.

They remember how the deck made them feel as a sequence.

To an investor, a deck is not 12–15 independent units. It’s a single cognitive journey with momentum, friction, and emotional shape. What matters is not whether one slide is excellent, but whether the flow between slides creates confidence.

This distinction becomes obvious once you understand how investors actually process information during a pitch review.

Investors Don’t Evaluate Slides — They Evaluate Transitions

When an investor finishes a slide, their brain immediately asks:

“Okay… what follows logically from this?”

If the next slide answers that question cleanly, momentum increases.

If it doesn’t, friction appears.

Repeated friction creates doubt.

This is why decks with “good slides” still fail. Each slide may be defensible in isolation, but if the transitions feel unnatural, investors subconsciously assume the founder’s thinking is fragmented.

Fragmented thinking raises real concerns:

Will this founder struggle when reality changes?

Are they reacting instead of driving?

Do they understand cause and effect?

Can they design systems, or only explain features?

Flow signals strategic maturity.

Flow Is How Investors Detect Strategic Coherence

Strategic coherence means your decisions make sense in relation to each other.

Flow is what makes coherence visible.

In mature decks:

The problem naturally leads to the solution

The solution naturally leads to traction

Traction naturally demands capital

Capital naturally accelerates something that already works

The future feels like a logical extension of the present

Nothing feels forced.

Investors don’t think, “That’s clever.”

They think, “That makes sense.”

That reaction is gold.

Founders underestimate how much investors value predictability of reasoning. Venture investing is fundamentally about risk. The more predictable your thinking appears, the more comfortable investors feel extrapolating forward.

Flow reduces perceived risk.

Poor Flow Is Interpreted as Poor Decision-Making

When slides jump abruptly between ideas, investors don’t consciously say:

“This deck has poor flow.”

Instead, they feel something subtler:

mild confusion

mental fatigue

loss of rhythm

weakened trust

They may not remember why they became skeptical — they only know that conviction didn’t form.

Common flow-breakers include:

jumping into metrics before explaining the engine

discussing fundraising mechanics before explaining why growth is constrained

showing vision before proving traction

introducing competition without context

mixing historical performance with future plans on the same slide

Each of these forces the investor to rearrange the story in their head — and most won’t bother.

When investors have to “work,” they disengage.

Flow Is Designed, Not Accidental

Strong flow does not come from copying decks.

It comes from thinking in systems.

Experienced founders implicitly ask:

“What does the investor need to believe right now?”

“What question is forming in their mind?”

“What uncertainty should I resolve next?”

“What tension can I introduce — and then relieve?”

Each slide either:

Resolves uncertainty

Introduces justified tension

Weak decks introduce tension accidentally and never resolve it.

Strong decks control tension deliberately.

The Best Decks Obey a Single Rule: Never Ask Investors to Hold Too Much in Their Head

Human working memory is limited.

Investors are especially sensitive to overload because they evaluate patterns continuously across deals. When a deck asks them to remember:

multiple definitions

several frameworks

competing narratives

disconnected metrics

…trust erodes.

Flow solves this by:

limiting each section to one core idea

reinforcing earlier assumptions instead of contradicting them

reusing framing consistently

escalating complexity gradually, not suddenly

This is why flow is often misdiagnosed as “simplicity.”

It’s not simple — it’s disciplined.

Flow Is the Difference Between “Interesting” and “Fundable”

Many decks are interesting.

Few are fundable.

“Interesting” decks introduce ideas.

“Fundable” decks move belief forward step by step.

By the end of a strong deck, the investor feels:

oriented

confident

ahead of the founder, not behind

ready to ask strategic questions

If an investor feels behind, they won’t invest.

If they feel ahead, they’ll want ownership.

Flow determines which side of that line you’re on.

How Flow Shapes the First Partner Conversation

This matters even more at partner meetings.

Partners don’t re-read decks carefully. They rely on:

the associate or partner presenting the deal

the clarity of the original narrative

how easily the story is retold

If your deck flows naturally, it survives retelling.

If it relies on explanation, it dies in internal discussion.

This is one of the most common silent failure points:

a founder nails the meeting, but the story doesn’t survive inside the firm.

Flow makes your story portable.

Portable stories get funded.

What Founders Get Wrong About “Reordering Slides”

When flow is weak, founders often try to fix it by rearranging slides.

This rarely works.

Why?

Because flow is not about order — it’s about logic.

If the logic is unclear:

changing slide order only reshuffles confusion

adding slides increases cognitive load

removing slides creates gaps

The real fix is upstream:

clarifying the causal chain

deciding what truly matters

choosing a dominant narrative

ruthlessly cutting secondary ideas

Once the thinking is coherent, flow becomes obvious.

Flow Is a Leadership Signal

At scale, founders don’t hand investors perfect information. They hand them structured reality.

Flow signals:

decision-making maturity

prioritization skill

system-level thinking

ability to guide others through uncertainty

These are CEO skills.

Investors are not asking whether your deck is pretty.

They’re asking whether you can lead a company through complexity without losing direction.

Flow answers that question quietly — but decisively.

Why This Section Matters More Than It Seems

Many founders think flow is a “nice-to-have.”

It’s not.

Flow is one of the highest-leverage improvements you can make because it:

increases comprehension

reduces skepticism

accelerates conviction

improves internal VC discussions

magnifies every strong signal you already have

Good data without flow stalls.

Average data with strong flow often gets funded.

That’s not unfair — it’s human.

One reason founders misread how a pitch is landing is simple: they experience the deck emotionally, while investors experience it diagnostically. The gap between those two perspectives is hard to see from inside the room. Some founders close that gap by stress-testing their decks outside live meetings — using structured analysis to surface clarity issues, cognitive overload, and signal mismatches before investor conversations happen.

Section 6 — The Unintentional Signals Founders Send During Pitch Delivery

By the time an investor reaches this stage of the pitch, they are no longer separating content from delivery.

Everything blends together.

What you say, how you say it, what you rush through, what you linger on—all of it becomes data. Not about the business, but about how you make decisions under pressure.

This is where many founders lose control of the room without realizing it.

They believe delivery is about confidence, energy, or charisma. Investors see delivery as something else entirely:

a live demonstration of how you think in real time.

Every pitch sends signals. Some are intentional. Most are not.

And the unintentional ones carry far more weight.

Investors Are Listening for Judgment, Not Performance

Founders often try to “perform well” in a pitch.

They rehearse lines.

They optimize phrasing.

They work on tone and pace.

But experienced investors are not evaluating theatrical confidence. They are listening for judgment under uncertainty.

They pay attention to:

how you respond when interrupted

whether your answers simplify or complicate

what you say when data isn’t perfect

whether you defend assumptions or examine them

how comfortable you are saying “I don’t know yet”

A founder who has strong delivery but weak judgment feels unstable.

A founder with calm judgment and imperfect delivery feels fundable.

This is counterintuitive, especially for first-time founders who assume polish equals credibility.

It doesn’t.

Judgment does.

Where Founders Accidentally Signal Immaturity

There are a few consistent patterns investors see again and again—signals that aren’t disqualifying on their own, but compound quickly.

Over-defense

When founders aggressively defend every assumption, investors sense rigidity. It suggests the founder hasn’t stress-tested their thinking internally and fears scrutiny.

Strong founders welcome pressure because they’ve already pressure-tested themselves.

Over-explanation

Talking longer than necessary to answer a question often signals uncertainty. Investors interpret this as lack of clarity, not thoroughness.

Clear thinkers answer precisely.

False certainty

Making absolute claims in uncertain environments (“this will definitely happen,” “customers always do this”) raises alarms. Venture outcomes are probabilistic. Investors trust founders who acknowledge uncertainty while still making decisive plans.

Emotional over-investment

Getting visibly attached to specific slides or narratives signals fragility. Investors want founders who can adapt, update, and reframe—not protect a fragile story.

None of these are fatal individually. Together, they form a pattern that experienced investors recognize instantly.

Delivery Is a Proxy for Leadership Behavior

The deeper reason delivery matters is this:

Investors extrapolate.

They assume that how you behave in a pitch reflects how you’ll behave:

in board meetings

during market shocks

when metrics decline

when tough trade-offs appear

when capital deployment decisions must be made quickly

The pitch becomes a compressed simulation of leadership behavior.

If a founder struggles to:

organize thoughts aloud

stay calm under questioning

prioritize what matters

acknowledge unknowns

…investors assume those weaknesses will amplify at scale.

Delivery is not evaluated in isolation. It’s evaluated as a leadership rehearsal.

The Role of Silence, Pace, and Restraint

Many founders fear silence.

They rush to fill every gap with explanation or reassurance. Investors notice immediately.

Silence, when used intentionally, signals confidence.

It shows:

comfort with the room

clarity of thought

willingness to let ideas land

respect for the listener’s intelligence

Similarly, pace matters.

Speaking quickly throughout a pitch often signals nervousness or overthinking. Speaking deliberately—slowing down when ideas matter—signals control.

Restraint is the throughline.

Restraint in words.

Restraint in claims.

Restraint in emotion.

Restraint tells investors you are not overwhelmed by complexity.

What Strong Delivery Actually Looks Like to Investors

To investors, strong delivery feels like:

calm clarity, not excitement

thoughtful answers, not rehearsed responses

measured conviction, not hype

openness to challenge, not defensiveness

ownership of uncertainty, not avoidance

The best founders rarely try to “win” the pitch.

They focus on aligning understanding.

They treat the pitch as a collaborative exploration:

“Here’s how we see the world. Tell me where you disagree.”

That posture changes the dynamic instantly.

Instead of being evaluated, the founder becomes a peer in reasoning.

This is where conversations shift from “pitch mode” to “investment dialogue.”

Why This Matters More Than Any Slide

Founders often ask:

“Can a bad delivery kill a good deck?”

The honest answer is yes—but not because of nerves.

Bad delivery kills good decks when it reveals:

shallow thinking

emotional fragility

lack of prioritization

discomfort with ambiguity

These traits don’t disappear after funding.

Investors are not avoiding awkward founders.

They are avoiding unpredictable decision-makers.

Strong delivery reassures them that even when things go wrong—and they will—the founder will stay grounded.

That reassurance is invaluable.

The Hard Truth Most Founders Miss

Founders often believe investors want to be impressed.

They don’t.

They want to feel safe being aligned with you.

Safe that:

you won’t chase noise

you won’t overreact

you won’t cling to bad ideas

you won’t freeze under pressure

you will keep making rational decisions

Delivery reveals that faster than any slide.

This is why veteran investors remember how a founder made them feel more than what the slides said.

Not emotionally.

Psychologically.

Delivery Is Not a Skill — It’s a Reflection

At the highest level, pitch delivery is not a performance skill.

It’s a reflection of:

how well you understand your business

how deeply you’ve thought through trade-offs

how comfortable you are with uncertainty

how much internal clarity you have

Founders who struggle with delivery usually don’t need coaching.

They need deeper internal alignment.

Once clarity exists internally, delivery becomes simple.

Not perfect.

But trustworthy.

And trust is the real outcome investors are evaluating.

Many of the signals investors pick up during delivery are not about confidence or polish — they come from structural inconsistencies founders don’t even realize they’re projecting. Things like uneven emphasis, unclear transitions, or slides doing too much cognitive work quietly distort how judgment is perceived. Founders who want to spot and fix these issues early often start by reviewing their deck the way investors do — slide-by-slide — using a clear framework that explains what each slide is actually meant to signal, not just what it says. VC pitch deck guide

Section 7 — The Q&A Is the Pitch (Slides Stop Mattering Here)

Many founders treat Q&A as something that happens after the pitch.

Investors don’t.

To an investor, the Q&A is the pitch. The slides are context. The conversation that follows is where conviction is built or destroyed.

This is where the real evaluation happens.

By the time questions start, investors already have an opinion forming. Q&A exists to test whether that opinion should harden or dissolve.

Founders misunderstand this and make a critical mistake: they try to “answer correctly.”

Investors aren’t scoring correctness.

They’re testing how you think under uncertainty.

What Investors Are Actually Testing During Q&A

During questions, investors are not hunting for gaps in your slides.

They are probing for:

how deeply you understand first-order vs second-order effects

whether your decisions are reactive or principled

how you reason when data is incomplete

whether you recognize trade-offs instead of hiding them

how you behave when challenged

Every question is less about the words you say and more about what your answers reveal about your operating mindset.

That’s why Q&A is ruthless.

Some founders with good decks unravel here—not because the business is weak, but because the thinking isn’t stable when examined closely.

Why “Perfect Answers” Don’t Matter

Founders often obsess over giving the “right” answer.

Experienced investors immediately distrust that.

They know startups aren’t deterministic systems. Any founder claiming perfect certainty discredits themselves.

What investors want to see instead:

clear logic

honest assumptions

awareness of constraints

comfort stating uncertainty

a plan for learning, not pretending

The strongest answers often include phrases like:

“We don’t know yet, but here’s how we’ll learn.”

“There’s a risk here, and here’s how we’re mitigating it.”

“If this assumption breaks, this is the adjustment we’d make.”

These answers feel grounded, not weak.

They signal a founder who operates in reality rather than fantasy.

Common Founder Mistakes During Q&A

There are predictable traps many founders fall into.

1. Over-answering

Founders speak too long, trying to cover every angle. This overwhelms investors and signals lack of clarity.

Strong founders answer narrowly, then pause.

2. Defensiveness

Taking questions personally or pushing back aggressively makes investors uncomfortable. It suggests fragility.

Strong founders treat questions as collaboration.

3. Over-indexing on edge cases

Trying to preempt every possible future problem derails the conversation.

Strong founders acknowledge risk without letting it dominate the narrative.

4. Slipping into sales mode

Using marketing language during Q&A signals insecurity. Investors want thinking, not persuasion.

The Subtle Power of How You Pause

One of the most underappreciated signals in Q&A is how long you pause before answering.

Rushed answers feel rehearsed.

Over-long pauses feel uncertain.

A measured pause suggests:

you’re considering the question seriously

you’re not relying on scripts

you’re choosing accuracy over speed

Investors notice this immediately.

It reads as intellectual honesty.

How Investors Use Q&A to Assess Founder Maturity

At a deep level, investors are asking themselves:

Would I want to sit across from this person in a board meeting?

Can this founder engage with doubt productively?

Do they listen—or just wait to speak?

Can they integrate new information in real time?

These are leadership questions.

Startups inevitably face moments where:

metrics contradict intuition

the strategy stops working

the market changes abruptly

capital must be allocated under pressure

Q&A is a compressed simulation of those moments.

Founders who respond calmly, logically, and transparently pass the test—even if their answers aren’t perfect.

Why Some Founders Win Investors Over During Q&A

Interestingly, many investment decisions don’t solidify during the pitch—but during Q&A.

This is where:

hesitation is addressed

trust is built

alignment forms

Investors may come in skeptical and leave convinced, not because the slides were flawless, but because the founder demonstrated sound reasoning when challenged.

Some of the strongest investor comments after a pitch sound like:

“The founder thinks clearly.”

“They were very honest in Q&A.”

“They didn’t dodge tough questions.”

“I trust how they reason.”

None of these comments reference slides.

Q&A Reveals Whether You’re Founder-Led or Ego-Led

One of the quiet judgments investors make is whether the founder is truth-led or ego-led.

Ego-led founders:

try to look correct at all costs

resist acknowledging uncertainty

deflect uncomfortable questions

overstate confidence

Truth-led founders:

adapt their thinking as the conversation evolves

admit limits without losing authority

ask clarifying questions back

treat the discussion as mutual exploration

Investors overwhelmingly prefer truth-led founders.

Because ego-led founders break under pressure.

Preparing for Q&A Is Not About Memorization

Founders often ask:

“How do I prepare for Q&A?”

The wrong approach is memorizing answers.

The right approach is:

deeply understanding your assumptions

knowing which variables matter most

being clear about risks and mitigation

aligning internally on decision logic

When you know why you’re doing something, answers emerge naturally.

Preparation creates flexibility, not scripts.

The Investor’s Quiet Checklist During Q&A

While listening, investors subconsciously check:

Is this founder coachable but not fragile?

Can they defend decisions without rigidity?

Do they understand what could go wrong?

Are they operating from principles or reactions?

Would I trust them with more information later?

If those boxes get checked, momentum builds.

If not, even a strong deck can stall.

Why Q&A Feels Harder Than the Pitch

Q&A strips away structure.

Slides give you control.

Questions remove it.

How you operate without control is deeply revealing.

This is why founders often say:

“The pitch went great, then Q&A got tough.”

From an investor perspective, that’s backwards.

Q&A didn’t “get tough” — it got real.

And real is what matters.

This is also why Q&A feels very different from pitching slides. Once the conversation begins, founders are effectively inside the VC decision process itself — where questions are used to test reasoning, not knowledge. Understanding how VC pitch decks are actually evaluated internally makes it much easier to handle this part of the pitch without defensiveness.

→ how VC pitch decks work

Section 8 — Why Most Investors Decide Before the Pitch Ends

One of the hardest truths for founders to accept is this:

Most investors form a directional decision long before the pitch is over.

Not a final decision.

Not a signed term sheet.

But a lean—yes, no, or wait.

Founders often assume that conviction happens at the end of the deck, after all the slides have been presented and all the questions answered. In reality, investors begin leaning much earlier, often within the first few minutes, sometimes even before the meeting starts.

This doesn’t mean the rest of the pitch doesn’t matter.

It means the rest of the pitch either confirms or reverses an early impression.

Understanding this changes how you should think about pitch delivery entirely.

How Early Judgments Form in an Investor’s Mind

Investors don’t consciously say, “I’ve decided already.”

What happens is subtler.

Early in the pitch, they start noticing:

whether the founder frames problems clearly

whether answers align with slides

whether logic compounds or drifts

whether the founder seems grounded in reality

These signals combine into a directional belief:

“This feels solid.”

or

“Something feels off.”

Once that belief forms, every subsequent slide is filtered through it.

If the belief is positive, investors give you the benefit of the doubt.

If it’s negative, they interrogate more aggressively—or disengage quietly.

This is why two founders can deliver similar content and receive wildly different outcomes.

Why Later Slides Often Can’t Recover a Bad Early Signal

Founders sometimes believe they can “win investors back” later in the deck with:

stronger traction

better unit economics

an exciting roadmap

Occasionally this works—but rarely.

That’s because early impressions tend to be about judgment, not data.

If investors perceive that:

the founder lacks clarity

the narrative feels reactive

the structure is unstable

the delivery is defensive

…then later data is viewed skeptically.

The investor’s internal reaction becomes:

“Even if the numbers look good, I’m not sure I trust how they’ll handle what comes next.”

Trust, once lost early, is extremely difficult to rebuild within a single meeting.

The Difference Between “Leaning Yes” and “Leaning No”

Early in a pitch, an investor might lean yes for reasons like:

the founder frames the problem with mature insight

the market is explained crisply

assumptions are surfaced, not hidden

delivery feels calm and controlled

They might lean no if:

explanations feel scattered

the founder over-defends

logic jumps without grounding

confidence feels performative rather than earned

These leanings are not emotional whims.

They’re pattern recognition.

Investors are constantly asking:

“Have I seen this type of founder succeed or fail before?”

The pitch is being compared—quietly—to past winners and losers.

Why the First Half of the Pitch Carries Disproportionate Weight

The early portion of the pitch does four critical things:

Sets the mental frame

It tells investors how to interpret what follows.Signals founder maturity

Before traction is discussed, investors assess how founders think.Establishes trust or doubt

Everything later is filtered through this lens.Determines engagement level

Leaning-yes investors ask exploratory questions. Leaning-no investors ask defensive ones—or go quiet.

This is why experienced founders are disproportionately careful with how they open and transition early sections.

They understand that the beginning defines the rules of interpretation.

What Changes When an Investor Is Leaning Yes

When an investor leans yes, their internal questions shift dramatically.

Instead of:

“Is this real?”

“What’s wrong here?”

“Why might this fail?”

They start asking:

“How big could this get?”

“Where does capital help most?”

“What risks would we want to manage early?”

“What kind of ownership would make sense?”

These are constructive questions.

They signal that the investor is now thinking in terms of alignment rather than evaluation.

The same slide content lands very differently depending on which mindset the investor is in.

Why Founders Misread Investor Behavior Late in the Pitch

Founders sometimes misinterpret late-stage engagement.

They think:

“They asked hard questions — that’s bad.”

or

“They were quiet — that’s good.”

Neither is reliably true.

Hard questions often mean engagement.

Silence often means disinterest.

What matters is why questions are being asked.

Are they clarifying to move forward?

Or are they poking holes to justify disengagement?

Founders who understand early leaning can read this more accurately and respond with confidence rather than anxiety.

Founders Rarely Control the Outcome — But They Control the Early Signal

It’s important to say this clearly:

You cannot force an investor to invest.

But you can control:

clarity of thinking

structure of reasoning

delivery under pressure

alignment between slides and answers

These are the inputs that shape early investor leaning.

When those inputs are strong, you give yourself the best possible odds.

When they’re weak, no amount of traction at the end of the deck can reliably save the pitch.

What This Means Practically for Founders

This section isn’t meant to create pressure or paranoia.

It’s meant to shift priorities.

Founders invest enormous time perfecting later slides—roadmaps, metrics, financials—while under-investing in:

early framing

logical sequencing

signal clarity

delivery discipline

Ironically, those early elements often matter more.

You don’t win investors by overwhelming them with strength at the end.

You win by earning trust early and then not breaking it.

The Quiet Skill Elite Founders Share

Founders who repeatedly raise capital develop a quiet skill:

They know when the room has already decided to lean in.

At that point, they stop selling.

They focus on clarity.

They invite discussion.

They listen carefully.

This behavior reinforces the very trust that caused the lean in the first place.

And that trust compounds.

Section 9 — How Investors Read Confidence (And Why Most Founders Get It Wrong)

Confidence in a pitch is one of the most misunderstood concepts in fundraising.

Most founders believe confidence means:

sounding certain

speaking assertively

minimizing doubt

projecting optimism

Investors interpret confidence very differently.

To them, confidence has almost nothing to do with tone or delivery style. It’s not about how loud you speak, how fast you respond, or how persuasive you sound.

Investor confidence is about internal alignment.

Specifically, it answers one question:

Does this founder understand what they know versus what they don’t—and are they behaving accordingly?

That distinction shapes everything.

The Two Types of “Confident” Founders Investors See

From an investor’s perspective, founders tend to fall into two broad categories:

1. Performance-based confidence

2. Judgment-based confidence

Performance-based confidence looks impressive initially:

strong delivery

polished answers

high energy

decisive statements

But it often collapses under scrutiny.

Judgment-based confidence is quieter:

calm explanations

precise wording

selective emphasis

willingness to acknowledge uncertainty

Investors overwhelmingly trust the second type.

Why?

Because startups operate in environments where certainty is impossible.

Confidence that ignores uncertainty feels disconnected from reality.

Confidence that accommodates uncertainty feels earned.

Why Overconfidence Is a Red Flag (Even When the Business Is Good)

Investors have seen this pattern too many times:

A founder presents an airtight narrative.

Every assumption is defended aggressively.

Every risk is waved away confidently.

On the surface, this can look impressive.

But internally, investors worry:

“What happens when reality disagrees with this story?”

“Will this founder adapt—or double down?”

“Are they protecting the narrative or the business?”

Overconfidence suggests rigidity.

Rigidity is dangerous at scale.

Investors don’t want founders who are always right.

They want founders who are right enough — and adaptable when wrong.

What True Confidence Actually Sounds Like

True confidence is expressed through boundaries.

It sounds like:

“This is the assumption we’re making — here’s why.”

“This part is still unclear, but we’re tracking it closely.”

“If this changes, our plan shifts in this direction.”

“We tested three options and this performed best.”

“This is a known risk; here’s how we’re mitigating it.”

To founders, this may sound cautious.

To investors, it sounds professional.

It signals:

realism

situational awareness

learning mindset

emotional stability

executive-level thinking

This is the kind of confidence investors back.

Why Confidence Is Read Through Structure, Not Claims

Founders often try to state confidence.

Investors look for it embedded in structure.

They ask:

Does the deck escalate logically?

Are assumptions placed before conclusions?

Are risks acknowledged before solutions?

Does the strategy adapt to constraints?

Confidence isn’t something you declare.

It’s something investors infer when your structure shows:

foresight

prioritization

respect for complexity

comfort with trade-offs

A deck filled with bold statements but weak structure feels hollow.

A deck with moderate claims anchored in strong logic feels trustworthy.

The Confidence → Trust → Conviction Chain

This section is critical because confidence is foundational.

Investor belief forms in a sequence:

Confidence → Trust → Conviction

Confidence: “This founder understands reality.”

Trust: “I believe how they’ll handle pressure.”

Conviction: “I’m willing to risk capital.”

If confidence is performative, trust never forms.

If trust doesn’t form, conviction won’t follow—no matter how strong the opportunity looks on paper.

This is why some technically strong startups struggle to raise. Their founders communicate certainty without clarity.

Investors sense the mismatch.

How Founders Accidentally Undermine Confidence

Many founders unintentionally weaken confidence through subtle behaviors:

Overcorrecting

Changing answers mid-sentence to sound stronger creates instability.

Avoiding risk discussion

The absence of risk acknowledgment feels unrealistic—not reassuring.

Overloading with data

Trying to “prove” confidence through volume suggests insecurity.

Contradicting earlier framing

Inconsistency erodes trust instantly.

None of these are fatal alone.

But together, they create doubt.

Investors rarely articulate this doubt clearly. They simply disengage.

Why Experienced Founders Feel “Calm” to Investors

You’ll often hear investors say:

“They feel like a second-time founder.”

This isn’t about pedigree.

It’s about how the founder relates to uncertainty.

Experienced founders:

don’t rush

don’t overreact

don’t oversell

don’t downplay risk

They operate from the assumption that uncertainty is normal, not threatening.

That posture signals confidence instantly.

This is the same posture VCs themselves adopt internally.

Founders who mirror it feel familiar—and therefore safer.

Confidence Is Not About Being Positive — It’s About Being Oriented

Founders often confuse confidence with optimism.

They’re not the same.

Optimism says:

“This will work.”

Confidence says:

“I understand why this might or might not work, and I’m prepared for both outcomes.”

Investors want the second.

Especially at early stages, realism beats positivity every time.

How Investors Test Confidence Without You Noticing

Investors don’t usually ask:

“Are you confident?”

They test it indirectly by:

pushing on weak assumptions

introducing counterexamples

questioning timelines

revisiting earlier claims late in the pitch

They’re watching:

whether your thinking holds

whether your tone changes

whether you become defensive

whether your reasoning stays consistent

Founders who pass this test rarely feel flashy.

They feel steady.

The Paradox of Investor Confidence

Here’s the paradox:

The less you try to project confidence, the more confident you appear.

This is because confidence is an output of clarity, not an input.

When your internal model of the business is coherent, confidence emerges naturally.

When it isn’t, no amount of performance can substitute.

That’s why this section belongs in Pillar 10.

Pitch delivery is not about selling belief.

It’s about revealing alignment between reality and decision-making.

Investors can feel when that alignment exists.

And when they do, conviction becomes possible.

Section 10 — Why Investors Care Less About What You Say Than What You Emphasize

Founders often assume investors are evaluating accuracy.

They’re not.

They’re evaluating judgment through emphasis.

At this stage of the pitch, most investors already accept that your facts are directionally correct. You wouldn’t be in the room otherwise. The real signal now is hidden in something more subtle:

What do you keep coming back to?

What do you slow down for?

What do you move past quickly?

These choices reveal how you rank importance in your own mind.

Emphasis Is the Clearest Window Into Founder Judgment

Every pitch contains far more information than an investor can assimilate in one sitting. Investors know this. That’s why they don’t rely on content completeness to assess founders.

They rely on signal weighting.

When a founder repeatedly emphasizes:

vision over execution details

narrative over mechanics

aspiration over constraints

…investors infer that prioritization in the business itself may follow the same pattern.

Conversely, when a founder emphasizes:

first-order drivers

system behavior

decision trade-offs

metric causality

…investors interpret this as operational maturity.

Emphasis is not about what’s on the slides.

It’s about where your attention naturally goes when explaining them.

Why Saying the “Right Thing” Can Still Send the Wrong Signal

Many founders prepare meticulously.

They rehearse strong lines.

They memorize talking points.

They optimize answers.

Ironically, this often weakens the very signal they’re trying to send.

Why?

Because rehearsed emphasis often feels flat.

When emphasis is authentic, it has rhythm:

ideas slow down when stakes rise

pauses appear near uncertainty

detail increases around decisions

abstractions thin out under scrutiny

When emphasis is rehearsed, everything receives equal treatment.

To investors, this feels off.

They can sense when a founder’s emphasis is shaped for persuasion rather than reflection.

Investors Watch for “Emphasis Drift”

One quiet test investors run is tracking consistency.

They notice:

does the founder emphasize the same drivers early and late?

do answers align with earlier framing?

does the importance hierarchy shift under pressure?

Emphasis drift is a red flag.

It suggests either:

unstable internal models

reactive thinking

emotional bias

or insufficient depth of understanding

Strong founders maintain emphasis coherence even when questioned aggressively.

They may adapt.

They may concede.

But their priority structure stays intact.

That stability builds trust.

The Difference Between Highlighting and Overselling

Highlighting is selective.

Overselling is compensatory.

Founders oversell when they:

repeat claims without new insight

add intensity without additional clarity

revisit points because they’re emotionally invested

chase conviction through volume

Investors interpret overselling as uncertainty.

Highlighting feels different.

It sounds like:

“This matters because it drives these outcomes.”

“This is where the risk concentrates.”

“This is what changes the equation.”

“Everything else is secondary to this.”

Notice the difference.

Highlighting simplifies.

Overselling multiplies.

Investors trust the founder who simplifies.

Why Emphasis Reveals How You’ll Allocate Capital

Ultimately, investors don’t care how you speak in a pitch.

They care how you will allocate:

time

capital

attention

regret

Emphasis is the only available proxy.

If you emphasize aesthetics over mechanics in a pitch, investors assume you may prioritize optics over fundamentals in the business.

If you emphasize growth without discussing constraints, investors worry about discipline.

If you emphasize vision without discussing trade-offs, investors question realism.

None of this is malicious.

It’s inferential.

Investors are doing their job: extrapolating limited data into long-term behavior.

Emphasis Changes How Risk Is Perceived

Two founders can describe the same risk.

One frames it as:

“This could be a problem, but we’ll deal with it later.”

The other frames it as:

“This is a risk we’re monitoring closely, and here’s what breaks if it doesn’t resolve.”

Same information.

Completely different emphasis.

The first sounds dismissive.

The second sounds in control.

Risk doesn’t scare investors.

Unexamined risk does.

How you emphasize risk signals whether you understand consequence, not whether you fear it.

What Investors Mean When They Say “The Founder Had Good Judgment”

After pitches, investors often summarize founders vaguely:

“Strong judgment”

“Sharp thinking”

“Clear priorities”

These phrases are responses to emphasis patterns, not technical detail.

Investors rarely remember the exact words you used.

They remember:

what you lingered on

what you skipped

what energized you

what you treated as obvious

From that, they infer:

“This is how this person will decide when things go wrong.”

That inference determines outcomes.

How Founders Accidentally Emphasize the Wrong Things

This usually happens for one of three reasons:

1. Emotional Attachment

Founders emphasize what they’re proud of, not what matters most.

2. Fear of Judgment

Founders over-emphasize strengths to compensate for perceived weaknesses.

3. Lack of Internal Clarity

Founders haven’t fully decided what truly matters yet.

None are moral failures.

But investors can tell the difference between conviction and confusion.

Emphasis as a Leadership Tell

In leadership contexts, emphasis shapes action.

Teams watch:

what leaders repeat

what they question

what they celebrate

what they ignore

Investors know this.

They assume your pitch behavior mirrors how you’ll lead internally.

That’s why emphasis matters more than articulation.

Good leaders don’t say everything.

They say the right things repeatedly.

The Founders Investors Remember

Investors remember founders who leave them thinking:

“They knew exactly what mattered.”

Not:

“They were articulate.”

“They were inspiring.”

“They were polished.”

Those are secondary.

“Knowing what matters” is rare—and extremely investable.

And that signal shows up first in emphasis.

Section 11 — The Silent Red Flags Investors Notice Before They Ever Say No

Most investor rejections don’t come from a single mistake.

They come from accumulation.

A slide that felt slightly off.

An answer that felt rehearsed.

A transition that felt forced.

An assumption that wasn’t examined carefully.

Individually, none of these kill a deal.

Together, they form a pattern.

And experienced investors are exceptionally good at pattern recognition.

This section matters because some of the most damaging pitch signals are never discussed openly. Investors won’t tell you:

“We passed because your judgment felt inconsistent.”

They’ll say:

“It wasn’t the right fit.”

Understanding these silent red flags is the difference between endlessly “almost-raising” and closing rounds efficiently.

Red Flags Are Rarely About the Business Itself

Founders often assume red flags are structural:

market too small

product not differentiated

traction insufficient

competition too strong

Sometimes they are.

But far more often, the red flags are behavioral signals embedded in how the founder presents and responds.

Investors know:

markets shift

products evolve

metrics improve

What’s harder to fix post-investment is decision-quality under pressure.

That’s what red flags really signal.

Red Flag #1: Inconsistency Across the Pitch

Inconsistency doesn’t always show up as contradiction.

It often emerges subtly:

a prioritization early that disappears later

a risk minimized on one slide and emphasized on another

aggressive growth claims paired with conservative execution plans

These small mismatches force investors to reconcile competing versions of the narrative.

Once reconciliation is required, trust begins eroding.

Strong founders don’t need to force consistency.

Their thinking already is.

Red Flag #2: Defensive Answering Patterns

Defensiveness is not about tone.

It’s about posture.

Defensive founders:

justify first, reflect later

frame questions as attacks

protect the narrative at all costs

resist alternative framings

Investors interpret this behavior instantly.

Not as confidence — but as fragility.

Defensiveness suggests that future corrections will be slow, emotionally charged, or resisted. In a venture context, that’s a deal-breaker.

Red Flag #3: Premature Certainty

Founders who sound too sure create discomfort.

Statements like:

“This always works.”

“Customers don’t really care about that.”

“That won’t be an issue for us.”

These aren’t reassuring.

They suggest the founder hasn’t lived through enough unexpected outcomes.

Experienced investors know certainty collapses quickly in real markets. They trust founders who speak in ranges, contingencies, and probabilities.

Premature certainty is interpreted as lack of exposure.

Red Flag #4: Obsession With Optics Over Mechanics

When founders spend more time explaining how something looks than how it works, investors notice.

Examples:

heavy focus on branding before retention is proven

excitement about surface metrics without unit economics

polished storytelling without operational depth

This doesn’t mean vision is bad.

It means misplaced emphasis is dangerous.

Optics without mechanics suggests a company optimized for narrative rather than longevity.

Red Flag #5: Avoidance of Trade-Off Language

Every startup operates through trade-offs.

Founders who avoid discussing them appear unrealistic.

Statements like:

“We don’t really have to choose.”

“We’re focused on everything right now.”

“There aren’t meaningful downsides.”

raise alarms.

Investors want to see founders articulate:

what they’re choosing not to do

what they’re sacrificing for speed or focus

what risks they’re temporarily accepting

Trade-off language signals ownership.

Avoiding it signals immaturity.

Red Flag #6: Over-Dependence on External Validation

Founders sometimes lean heavily on:

logos

advisors

pilot partners

statements of interest

External validation is useful.

Over-dependence is not.

When founders rely on third-party credibility rather than their own reasoning, investors question autonomy.

Investors back decision-makers, not validators.

Red Flag #7: Emotional Volatility Under Light Pressure

Investors don’t need founders to be calm all the time.

They need them to be stable.

Microscopic emotional shifts matter:

visible frustration

irritation at follow-up questions

abrupt tone changes

rushed defensiveness

These signals extrapolate forward.

If pressure here creates volatility, pressure later will magnify it.

Why Investors Rarely Explain These Red Flags

Founders often wonder why feedback is vague.

The reason is simple: these signals are not always articulable.

They are felt.

Investors operate on experience-heavy pattern recognition. Explaining instinctive discomfort is hard — and often perceived as personal criticism.

So investors pass quietly.

Understanding red flags lets founders self-correct before feedback is necessary.

The Difference Between First-Time and Repeat Founders

Repeat founders don’t necessarily avoid all red flags.

They recover faster.

When inconsistency appears, they clarify.

When questioned, they reflect instead of defending.

When uncertainty surfaces, they navigate it openly.

Investors sense this immediately.

It’s not perfection that matters.

It’s adaptability.

Red Flags Accumulate Quietly, Not Dramatically

Very few pitches implode.

Most simply lose energy.

Questions become sparse.

Follow-ups slow.

Introductions stop.

This is what happens when red flags stack silently.

Recognizing them early allows founders to intervene — in narrative, structure, and delivery — before momentum is lost.

What This Section Is Really Teaching

This section isn’t meant to create fear.

It’s meant to increase awareness.

Red flags don’t mean failure.

They mean misalignment.

And misalignment is fixable — before and during the pitch — if founders understand what investors are actually reacting to.

That awareness alone separates founders who stall from founders who close.

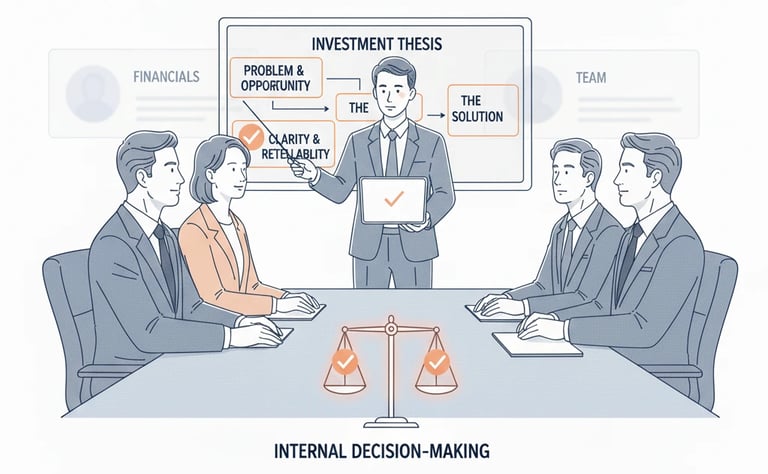

Section 12 — How Pitch Delivery Shapes the Internal VC Conversation You’ll Never Hear

Founders often assume the pitch is over when the meeting ends.

For investors, the pitch only begins then.

What determines whether a deal progresses is not what was said in the room—but how the story survives after you leave. Inside venture firms, decisions are rarely made by the person you pitched alone. They are made collectively, in rooms you never see, by people who were not present at the meeting.

This is where pitch delivery quietly becomes decisive.

Because delivery determines whether your story can be retold accurately, convincingly, and without distortion.

The Real Audience of Your Pitch Is the Investment Committee

Even if you pitched:

a partner

a principal

an associate

…your true audience is the entire partnership.

That audience will never hear your voice.

They will never see your demeanor.

They will never feel your energy.

They will only hear a secondhand reconstruction of your thinking.

The question every investor implicitly asks themselves after your meeting is:

“Can I explain this company clearly to my partners?”

If the answer is no, momentum stalls—regardless of how compelling the pitch felt live.

Why Founders Misinterpret “We’ll Discuss Internally”

When investors say:

“We’ll take this back to the team.”

Founders often hear hope.

But internally, that sentence means:

“Let’s see if this story holds up without the founder in the room.”

Most stories don’t.

Not because the founders were weak—but because the reasoning was too dependent on delivery.

If the insight only worked when you said it, it doesn’t work.

How Delivery Translates Into Internal Story Strength

Inside the firm, whoever heard the pitch must answer questions like:

What problem are they really solving?

Why does this solution work now?

Where does growth come from?

What breaks first?

Why this founder?

What’s the biggest risk?

Where does ownership make sense?

Your delivery determines whether these answers feel:

crisp or muddy

confident or qualified

structured or scattered

If explaining your company requires caveats, hedging, or emotional qualifiers—investors hesitate.

They don’t want to sell complexity to their partners.

They want a story that stands on its own logic.

Why “Charisma” Disappears Inside the Firm

Charisma doesn’t travel.

Presence doesn’t travel.

Tone doesn’t travel.

Only structure and reasoning do.

This is why overly performative pitches fail internally. The energy vanishes, leaving behind fragile logic.

Strong delivery isn’t charismatic.

It’s portable.

It creates a narrative that survives summarization.

The Silent Question VCs Ask After Your Pitch

When the meeting ends, investors often sit quietly for a moment.

Then someone asks:

“Okay… what do we actually think?”

At that point, delivery has already done its job or failed.

Founders who delivered clearly have enabled:

aligned recall

shared mental models

agreement on key risks and drivers

Founders who relied on performance leave behind:

fragmented impressions

differing interpretations

uncertainty about core assumptions

Disagreement isn’t bad.

Confusion is.

Why Associates and Principals Are the Real Gatekeepers

Most early-stage deals are championed by:

associates

senior associates

principals

These are the people who:

summarize your pitch

write the internal memo

frame the partner discussion

If your delivery helped them understand:

what matters

what doesn’t

what’s next

They advocate strongly.

If not, your deal becomes “interesting but unclear.”

Unclear deals die quietly.

How Investors Decide Whether to Push the Deal Forward

Inside the firm, the decision is rarely:

“Is this amazing?”

It’s usually:

“Do I feel confident sending this to IC?”

Confidence comes from:

clarity of logic

coherence of strategy

believability of execution

maturity of reasoning

Delivery during the pitch is what signals whether that confidence exists.

The Founder Skill That Changes Everything

Exceptional founders understand one thing:

They’re not pitching a deck—they’re pitching a model of reality.

If, after they leave the room, investors can say:

“This makes sense.”

“I get the trade-offs.”

“I understand the risk.”

“I know what matters most.”

Then the story lives.

If not, no amount of charm can save it.

Why This Explains Many “Mystery No’s”

Founders often say:

“The meeting felt great, but then nothing happened.”

This section explains why.

The pitch worked live—but collapsed internally.

That collapse almost always traces back to:

compressed reasoning

fragile structure

delivery-dependent logic

Fixing this changes outcomes more than adding slides ever will.

The Ultimate Goal of Pitch Delivery

The highest goal of delivery is not persuasion.

It’s exportability.

You win when investors can:

explain your company without you

defend it without caveats

advocate for it convincingly

That’s how deals move.

That’s how momentum builds.

That’s how funding happens.

Section 13 — Why Pitch Delivery Is a Test of Executive Presence, Not Presentation Skill

By the time founders reach this stage of maturity, one truth becomes unavoidable:

Pitch delivery is not a communication skill.

It is a leadership signal.

Investors don’t expect founders to be polished speakers. They expect them to exhibit executive presence—the ability to command attention, maintain clarity, and make decisions feel grounded under pressure.

This distinction explains why some founders with mediocre presentation skills raise easily, while others with flawless slides struggle.

What investors are really evaluating is not how well you present, but who you appear to be when the presentation is no longer carrying you.

What Executive Presence Means to Investors

Executive presence is not confidence in the performative sense.

It’s not volume.

It’s not charisma.

It’s not intensity.

To investors, executive presence means:

calm authority under ambiguity

clarity under questioning

emotional stability under scrutiny

comfort making imperfect decisions

awareness of one’s own limitations

This is the presence of someone who will run a company through volatility.

During a pitch, presence emerges most clearly in:

how you handle interruptions

how you respond to disagreement

how quickly you recalibrate explanations

how you choose what not to answer

These moments are rarely rehearsed—which is precisely why they’re informative.

Why Slides Can Hide Weak Presence—Until They Can’t

Early in the pitch, slides provide structure, cadence, and confidence.

But as the conversation progresses—especially into Q&A—slides fade into the background.

That’s when presence takes over.

Founders with weak presence often:

lean heavily on slides to regain footing

retreat into rehearsed language

avoid direct engagement

over-intellectualize simple questions

Investors notice immediately.

It suggests the founder hasn’t fully internalized the business yet—they are still explaining it to themselves.

Strong presence shows the opposite: the founder is no longer dependent on the material.

How Investors Distinguish Presence from Confidence

This distinction is subtle but critical.

Confidence is outward-facing.

Presence is inwardly anchored.

Confident founders may sound strong until something unexpected happens. Presence reveals itself when plans are disrupted.

Investors test this intentionally:

They change the direction of questions

They introduce alternative interpretations

They challenge assumptions unexpectedly

They question something the founder thought was settled

These aren’t attacks—they’re diagnostics.

Founders with presence don’t defend reflexively. They:

pause

consider

respond proportionally

integrate new information calmly

That calm integration is what investors are seeking.

Why Executive Presence Scales—and Presentation Skill Doesn’t

Presentation skill helps you convince a room once.

Executive presence helps you:

lead teams

navigate board meetings

manage crises

make unpopular trade-offs

course-correct decisively

Investors are not betting on pitches—they are betting on five to ten years of leadership behavior.

Pitch delivery is simply the earliest observable sample.

Founder Behavior That Signals Strong Executive Presence

Investors consistently associate presence with founders who:

speak with precision instead of volume

acknowledge uncertainty without apology

respond directly rather than emotionally

avoid over-explaining

prioritize what matters in real time

This is not something founders fake successfully.

Presence comes from deep internal clarity:

clarity about priorities

clarity about risks

clarity about unknowns

clarity about decision logic

Without that clarity, presentation techniques collapse under stress.

Why Many First-Time Founders Struggle Here

First-time founders often interpret executive presence as something they lack by default.

That’s a mistake.

They struggle not because they lack experience, but because they haven’t yet resolved internal ambiguity.

Ambiguity inside the founder manifests externally as:

inconsistent answers

shifting emphasis

nervous pacing

over-explanation

None of this is surprising.

Presence emerges once a founder has made peace with:

what they know

what they don’t

what matters most

what they’re willing to learn over time

This is an internal alignment problem—not a talent one.

Why Investors Trust Founders Who Don’t Perform

Some of the strongest investors will tell you:

“The best founders don’t feel like they’re pitching.”

They feel like they’re thinking out loud carefully.

This is presence.

It creates space for dialogue instead of pressure for persuasion.

Investors relax.

The conversation deepens.

Trust starts forming.

Not because the founder tried harder—but because they stopped performing.

How Presence Shapes the Long-Term Founder-Investor Relationship

Investors don’t just ask:

“Can I fund this person?”

They ask:

“Can I work with this person for the next decade?”

Presence in the pitch signals:

openness to challenge

ability to handle disagreement

emotional resilience

rational decision-making

These are exactly the traits that determine whether future board meetings are productive—or painful.

Founders who show presence early create smoother long-term relationships.

The Misleading Advice Founders Often Receive

Founders are often told to:

“Be more confident”

“Show more passion”

“Sell the vision”

This advice is incomplete—and often harmful.

It encourages performance instead of grounding.

Investors don’t need more enthusiasm.

They need more orientation.

Orientation answers:

where are we?

why here?

what matters now?

what happens next?

Founders who deliver orientation feel credible.

What Executive Presence Looks Like in Its Purest Form

At its core, executive presence feels like:

“This person can navigate complexity without losing direction.”

When investors feel that, everything else becomes secondary.

Slides can improve.

Metrics can change.

Markets can shift.

Presence is harder to manufacture later.

That’s why it carries so much weight in pitch delivery.

The Quiet Outcome of Strong Executive Presence

Founders who demonstrate presence often leave meetings with:

fewer objections

more thoughtful questions

faster follow-ups

internal investor champions

Not because they persuaded harder—but because they felt trustworthy.

And in venture investing, trust is the foundation of conviction.

Section 14 — How Great Founders Use the Pitch to Establish Long-Term Authority

By this stage in the pitch, something important is happening beneath the surface:

The pitch is no longer about this round.

For experienced investors, it has quietly become about whether they believe in you over time.

Founders who understand this distinction behave very differently from those who don’t.

They stop treating the pitch as a transaction and start using it as a positioning moment—a way to establish authority that lasts beyond a single meeting.

This is where many first-time founders miss the opportunity entirely.

Investors Are Not Just Backing a Company — They’re Entering a Long Relationship

A venture investment is not momentary.

It can involve:

years of collaboration

repeated decision-making under stress

strategic disagreements

capital allocation debates

hiring conflicts

moments where only trust holds things together

At this point in the pitch, investors are subconsciously asking:

“How will this founder show up over time?”

This is not answered by slides.

It’s answered by how you frame decisions, uncertainty, and responsibility throughout the conversation.

Authority Is Not Claimed — It Is Positioned

Founders sometimes believe authority comes from:

naming big advisors

referencing known investors

highlighting press or logos

Those are signals, but they’re shallow ones.

Real authority is inferred when a founder:

frames problems cleanly

owns decisions without ego

explains trade-offs with clarity

acknowledges limits without discomfort

demonstrates independent thinking

Investors recognize authority not through declaration, but through orientation.

An authoritative founder helps investors understand:

what really matters

what doesn’t

what’s controllable

what isn’t

and why the chosen path is rational

Why Authority Changes the Power Dynamic in the Room

When authority is present, the room feels different.

The pitch turns from:

“Convince me.”

into:

“Let’s think this through together.”

Questions shift from skepticism to curiosity.

Tone shifts from evaluation to collaboration.

This is where funding stops feeling like approval—and starts feeling like alignment.

Founders who establish authority early:

face less adversarial questioning

receive more constructive input

experience smoother negotiations

gain internal champions

Authority reduces friction.

How Authority Shows Up in Language and Framing

Authority is often expressed through small, repeatable habits:

Using precise language instead of dramatic claims

Framing decisions as trade-offs instead of absolutes