Pillar 12 — Tools, Templates & Examples

Section 1 — Why Tools & Templates Don’t Replace Judgment (And How Investors See Through It Instantly)

Founders often believe tools and templates exist to reduce thinking.

Investors believe the opposite.

To an investor, tools are not shortcuts—they are revealers. They expose how a founder reasons, what they outsource mentally, and where judgment is weak or strong. This is why two founders can use the exact same template and get radically different reactions. One earns confidence. The other triggers hesitation.

The difference is not the tool.

It’s the judgment layered on top of it.

Why investors don’t “hate templates” (they hate unexamined thinking)

There’s a lazy narrative in startup culture that investors dislike templates. That’s not true.

Investors dislike:

founders who confuse structure with insight

founders who mistake completeness for clarity

founders who lean on polish to cover uncertainty

Templates themselves are neutral. They are scaffolding.

What investors react to is whether the founder:

understands why each section exists

knows what trade-offs the structure is forcing

can explain deviations deliberately

A template used intentionally signals discipline.

A template used blindly signals dependency.

And dependency is one of the biggest early-stage risks investors evaluate.

How investors detect “template thinking” in minutes

Most founders think investors need time to notice this.

They don’t.

Experienced investors spot template thinking within the first few slides because the signals are consistent:

identical phrasing across decks

sections that exist but don’t say anything

generic metrics with no decision context

slides that answer “what” but not “why”

design cohesion without narrative cohesion

These decks feel technically correct but mentally hollow.

Investors don’t think, “This founder used a template.”

They think:

“This founder hasn’t formed independent judgment yet.”

That distinction matters.

Why tools amplify judgment instead of replacing it

Tools don’t eliminate judgment—they amplify whatever judgment already exists.

If a founder has:

clear mental models

strong command of trade-offs

realistic understanding of uncertainty

tools make that thinking easier to communicate.

If a founder lacks those things, tools simply scale confusion faster.

This is why investors sometimes prefer rough decks:

messy but coherent beats polished but vague

flawed logic is fixable; absent logic is not

The tool makes the thinking visible. That’s all it does.

The investor’s invisible question when reviewing tool-heavy decks

When investors see a deck built perfectly to a known framework, they quietly ask:

“Does this founder know where they’re relying on the tool—and where they’re thinking for themselves?”

They look for:

moments of deliberate deviation

choices that don’t “optimize for beauty”

prioritization that fits this startup specifically

Uniformity is not reassuring.

Specificity is.

Why over-tooled founders feel brittle under pressure

A common investor fear is not incompetence—it’s fragility.

Founders who rely too heavily on tools often struggle when:

assumptions are challenged

numbers don’t line up

a slide doesn’t support the claim

comparisons fall apart

They’ve learned how to assemble materials, but not how to defend reasoning.

Investors sense this quickly.

They’re not worried about today’s deck.

They’re worried about tomorrow’s decisions.

Tools change how founders explain, not what they understand

One subtle but critical distinction:

Tools change presentation speed.

Judgment changes decision quality.

Founders who over-trust tools:

explain outputs confidently

struggle to explain inputs clearly

Founders with strong judgment:

can explain assumptions without slides

use tools to compress, not replace, understanding

Investors trust the second group—always.

Why copying “best-in-class” tools backfires

Another founder mistake is chasing whatever tools “successful startups” used.

This ignores context:

market timing

competitive density

fund expectations

stage-specific risk

Copying tools without copying thinking frameworks produces shallow similarity.

Investors notice immediately when a deck looks familiar but feels misaligned.

Familiarity without fit is a red flag.

The mental shift this pillar requires

This pillar is not about collecting resources.

It’s about replacing the question:

“Which tools should I use?”

With:

“What decisions am I responsible for—and where can tools support that responsibility?”

Once founders make this shift:

tools become leverage

templates become accelerators

examples become references, not crutches

And investor trust rises accordingly.

What this section sets up for the rest of Pillar 12

Everything that follows builds on one truth:

Tools don’t create confidence.

Clarity does.

The upcoming sections will show:

when templates help vs hurt

how investors interpret tool choices

how examples should be mined (not copied)

how to use modern tools—including AI—without signaling immaturity

But it all starts here.

Judgment first. Tools second.

Founders who want a structured way to apply judgment across pitch decks, sales decks, and financial models often rely on a VC-ready pitch system designed to support investor-grade decision making without hiring a traditional consultant.

Section 2 — The Right Way to Use Pitch Deck Templates (Structure Without Surrendering Thinking)

Pitch deck templates exist for a reason.

They reduce friction.

They impose order.

They prevent founders from missing obvious sections.

But this is where most founders misunderstand their role.

Templates are containers, not conclusions.

Used correctly, they speed up clear thinking.

Used incorrectly, they outsource it.

Investors can tell which happened almost immediately.

Why templates exist in the first place

Templates weren’t created to make decks “look investor-ready.”

They were created to solve three recurring problems:

founders skipping essential context

incoherent ordering of ideas

inconsistent depth across sections

Templates bring baseline completeness.

Nothing more.

They do not:

decide what matters most

prioritize trade-offs

calibrate ambition

contextualize risk

Those are judgment tasks. Templates can’t solve them.

How investors interpret template-heavy decks

When investors recognize a familiar template, their reaction is not negative.

It’s neutral.

What happens next determines everything.

They start scanning for:

where this founder followed the template rigidly

where they intentionally deviated

what the deviations reveal about thinking

Investors want to see selective non-compliance.

Founders who apply the template perfectly but add nothing unique appear interchangeable.

Interchangeable founders feel risky.

The difference between “structure-first” and “template-first” founders

This distinction is subtle but decisive.

Template-first founders:

fill in every section equally

assume completeness equals quality

optimize for symmetry

avoid killing weak sections

Structure-first founders:

understand the logic behind each section

deepen what matters

compress or remove what doesn’t

treat the template as negotiable

Investors back structure-first founders.

Because structure reveals intention.

What founders should customize vs what should stay stable

Templates work best when certain elements remain stable:

overall storyline flow

investor logic order

core evaluation checkpoints

But founders should actively customize:

depth per section

emphasis based on stage

sequencing where logic demands

explanatory density around risk

If every section in your deck feels equally important, investors assume you haven’t prioritized yet.

And lack of prioritization is often read as early-stage immaturity.

Why “famous deck templates” are often misused

Founders love copying decks from successful companies.

Investors are wary of this.

Not because examples are bad — but because founders often copy:

phrasing without context

slide order without rationale

confidence without constraint

What they fail to copy is timing.

Successful decks worked because:

markets were ready

competition was sparse

investors already believed the narrative

Removing those conditions and keeping the structure creates false confidence signals.

Investors may recognize the template, but they don’t transfer the credibility.

How investors test whether a template helped or hurt

Investors ask probing questions not to learn facts, but to see:

whether the founder can defend the structure

whether they know why something was included

whether they can reposition the story verbally

If the founder struggles without the slides, the template has overpowered understanding.

That’s a serious concern.

Investors need founders who can think without scaffolding — even while using it.

Why over-complete decks raise suspicion

Another common mistake is including everything “just in case.”

Templates encourage this.

Over-complete decks:

hide weak conviction behind volume

signal uncertainty in prioritization

slow investor scanning

Investors don’t reward thoroughness.

They reward decisive clarity.

A founder who knowingly removes a slide often looks stronger than one who keeps it “just to be safe.”

The subtle confidence signal investors respect

The strongest signal a template-trained founder can send is restraint.

Examples:

skipping a slide because it’s irrelevant at this stage

collapsing sections intentionally

deferring metrics instead of forcing precision

These choices say:

“I know the framework — and I know where it breaks.”

That combination earns trust.

How founders should think about templates going forward

Replace this mindset:

“This template ensures I cover everything.”

With this one:

“This template reveals where I must decide.”

Every slide exists because someone once thought it mattered.

Your job is to decide whether it still does — for your company, now.

That decision process is what investors evaluate.

Not the slide itself.

Core takeaway for Section 2

Templates help founders move faster — but only founders who already know where they’re going.

For everyone else, templates create momentum without direction.

Investors fund direction.

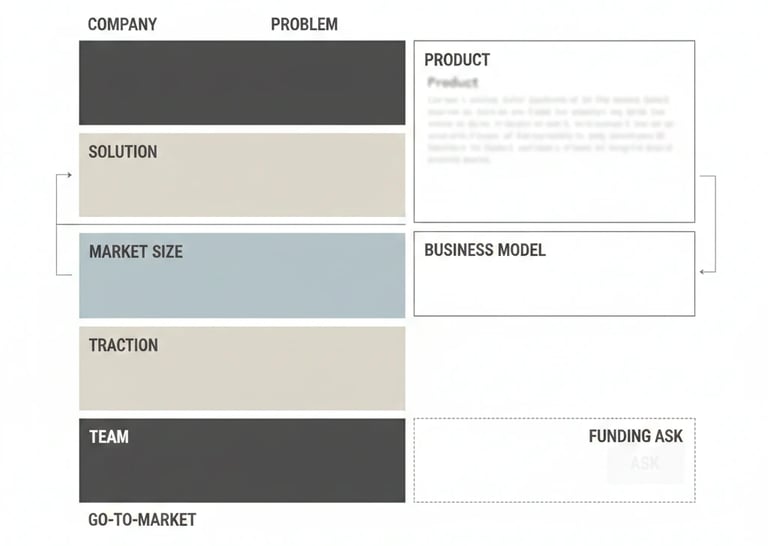

This logic is rooted in slide structure frameworks that reflect how investors scan, interpret, and judge pitch decks under time pressure.

Section 3 — What Investors Mean by “Comparable Decks” (And Why Misreading Examples Backfires)

When investors say,

“We’ve seen decks like this before,”

most founders hear reassurance.

What investors actually mean is:

“We’ve formed expectations — and your deck will now be judged against them.”

Comparable decks are not inspiration.

They are benchmarks.

Misunderstanding this distinction is one of the quietest ways founders weaken their position without realizing it.

How investors actually use comparable decks

Investors don’t study examples to admire them.

They use decks comparatively to answer three internal questions:

how quickly can this be understood versus others?

how does this opportunity rank against similar bets?

where does this startup underperform relative to peers?

Every deck enters a mental stack.

Founders rarely realize they are not competing against nothing — they are competing against recent memory.

Why comparables are internal, not public

Founders often search for public examples: blogs, Medium posts, or famous decks.

Investors rarely think about those.

Their true comparables come from:

current deal flow

recent passes

internal retrospectives

past investments that succeeded or failed

These examples are contextual, not inspirational.

Copying public decks doesn’t help founders match the actual comparison set being applied internally.

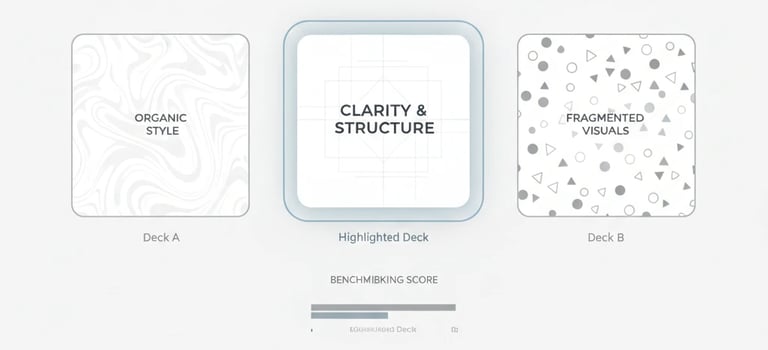

What investors compare — and what they don’t

Investors don’t compare aesthetics first.

They compare:

clarity of positioning

decision logic per slide

signal density

risk articulation

narrative efficiency

A beautiful deck that explains less feels worse than a rough one that explains precisely.

Founders who optimize for visuals alone often fall behind in invisible comparisons.

Why copying structure without context fails

Founders often think:

“If this structure worked for them, it should work for us.”

This ignores four variables investors subconsciously factor:

market maturity

competitive density

fund thesis alignment

stage expectations

Two identical structures can signal strength or weakness depending on context.

Investors assume founders understand this.

When they don’t, confidence erodes quietly.

The danger of survivorship bias in examples

Most example decks founders study come from companies that won.

Investors know this is deceptive.

They’ve seen hundreds of decks that looked similar and lost.

When founders rely heavily on survivor examples, investors worry:

“Is this founder learning from outcomes instead of decisions?”

Sound judgment focuses on process, not winners.

How investors spot imitation instantly

Founders assume investors are overwhelmed and won’t notice reuse.

In reality, investors experience repetitive pattern recognition daily.

They notice:

reused phrasing

familiar slide ordering

borrowed metaphors

recycled analogies

Imitation signals speed, not depth.

Depth earns trust.

What investors actually respect in example usage

Examples become valuable when founders use them to:

explain decisions, not justify them

contrast approaches, not copy them

show awareness of constraints, not ambition alone

An investor responds far better to:

“We considered this approach used by X, but rejected it because…”

than:

“We’re following the same model as X.”

The first shows thinking.

The second shows dependency.

How to extract value from examples without copying

Founders should study examples by asking:

what question was this slide solving?

what risk was this structure addressing?

what investor doubt was being neutralized?

Then they should:

discard the surface expression

retain the underlying logic

rebuild it for their context

This process creates originality without inventing from scratch.

Why comparables raise the bar, not lower it

Many founders feel relieved when they resemble others.

Investors feel the opposite.

Similarity increases scrutiny.

If your deck resembles others, the expectation rises that:

explanations be sharper

assumptions be tighter

trade-offs be clearer

Blending in is not safety.

Precision is.

Core takeaway for Section 3

Comparable decks don’t protect you.

They compete with you.

Investors don’t want familiarity—they want justified differentiation.

Use examples to sharpen thinking, not to borrow certainty.

To understand this comparison process, it helps to see how VCs evaluate pitch decks internally across screening, filtering, and discussion stages.

Section 4 — Tools Investors Respect (And Tools That Quietly Raise Skepticism)

Founders often assume investors judge what tools they use.

In reality, investors judge why those tools were chosen—and how they’re used.

To an investor, tools are not productivity aids.

They are signals of maturity, control, and decision discipline.

Two founders can use the same stack and send opposite messages.

Why tools act as proxies for operational thinking

Investors know early-stage startups are messy.

They don’t expect perfect systems.

They expect intentional ones.

Every tool choice signals something:

what the founder values

how complexity is managed

whether clarity or speed is prioritized

how decisions flow through the company

Tools don’t prove competence.

They expose assumptions.

The tools that quietly earn investor respect

Tools investors tend to respect share common traits:

they simplify communication

they reduce ambiguity

they surface reality early

Examples include:

clean documentation systems over flashy dashboards

simple forecasting models over hyper-detailed spreadsheets

shared decision logs over polished task boards

Investors interpret these as signals of:

control over narrative

clarity over theater

discipline over impressiveness

These tools don’t look impressive at first glance—but they age well.

Tools that often raise silent skepticism

Some tools raise concern not because they’re bad—but because they’re often misused.

Common patterns that worry investors:

over-automated insight tools with no explanation layer

sophisticated analytics without clear decision linkage

bloated stacks early in the company lifecycle

tools adopted because “other startups use them”

Investors read these as signs of outsourced thinking.

They wonder:

“If pressure increases, will this founder understand what the system is saying—or just follow it?”

That doubt matters.

Why excessive tooling feels like fragility

More tools often create less confidence.

When a founder relies on many systems, investors worry about:

brittle workflows

hidden dependencies

slow decision cycles

diffusion of responsibility

Simplicity suggests mastery.

Complexity demands explanation.

If the story behind the tools isn’t clear, investors assume it won’t hold under stress.

How stage dramatically alters tool perception

Context matters more than the tool itself.

A tool that feels appropriate at Series A can feel premature at pre-seed.

Investors adjust expectations based on:

company maturity

team size

revenue predictability

operational risk

Using “later-stage” tools too early often signals imitation rather than readiness.

Using simple systems well, early, signals restraint.

And restraint is a confidence marker.

The strongest signal: explanation without defensiveness

When investors ask,

“Why did you choose this tool?”

They’re not testing knowledge.

They’re testing:

clarity of reasoning

awareness of alternatives

willingness to revise

Founders who answer calmly and precisely:

“This helps us see X risk earlier, even though it sacrifices Y”

sound credible.

Founders who justify tools emotionally—

“Everyone uses this” or “It’s best practice”

sound fragile.

Tools as communication layers, not engines

Investors care less about what powers decisions and more about what communicates them.

The founder who can:

explain choices without dashboards

reduce systems to insights

speak without hiding behind software

is trusted more than one who needs tools to sound confident.

Tools that clarify reasoning beat tools that generate noise.

What investors don’t expect from tools

They do not expect:

automation to replace judgment

metrics to eliminate trade-offs

dashboards to solve uncertainty

Investors expect founders to own outcomes, not delegate them to systems.

Tools support judgment.

They never absolve it.

Core takeaway for Section 4

Investors don’t prefer advanced tools.

They prefer appropriate tools used deliberately.

When tools simplify thinking, confidence rises.

When they obscure it, skepticism follows.

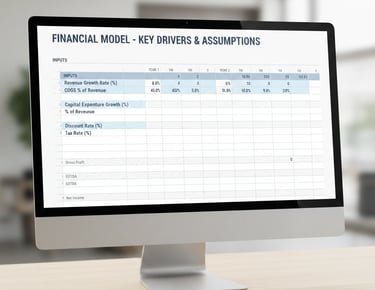

Section 5 — Financial Model Templates: When They Help — and When They Quietly Undermine Trust

Financial model templates are one of the most misunderstood tools in fundraising.

Founders often treat them as proof of rigor.

Investors treat them as windows into how a founder thinks about uncertainty.

A clean model doesn’t impress investors by itself.

What impresses them is whether the logic behind the model survives pressure.

This is where templates either help—or hurt.

Why investors rarely read financial models the way founders expect

Most founders believe investors will:

check formulas

validate projections line by line

reward completeness

In reality, early-stage investors skim models to answer different questions:

Do the assumptions make sense together?

Does growth logic feel internally consistent?

Is uncertainty acknowledged or suppressed?

Does the founder understand what actually drives the business?

A model is not a math exercise.

It’s a decision narrative expressed in numbers.

Templates don’t write that narrative for you.

When financial templates genuinely help founders

Templates are useful when they:

enforce logical discipline

prevent structural mistakes

provide a baseline for scenario thinking

Good use cases include:

ensuring revenue, costs, and cash connect coherently

stress-testing assumptions quickly

forcing founders to specify drivers instead of vibes

In these cases, templates act as thinking constraints.

They don’t decide outcomes.

They make weak assumptions visible earlier.

When templates actively damage credibility

Templates become dangerous when founders:

accept default assumptions without altering them

force numbers to “look VC-ready”

smooth volatility to avoid difficult questions

project false precision far into the future

Investors recognize this instantly.

They don’t assume optimism.

They assume avoidance.

A model that looks too clean often signals a founder who hasn’t grappled deeply with risk.

Why false precision raises more concern than rough estimates

One of the strongest investor red flags is precision without justification.

Examples that trigger skepticism:

detailed monthly projections 3–5 years out

exact CAC improvements without clear levers

neatly compounding growth curves disconnected from operations

Investors know the future is uncertain.

Founders who pretend otherwise appear either inexperienced or unwilling to confront reality.

Ironically, rough ranges often feel more credible than perfect numbers.

What investors actually test in financial templates

When investors open a model, they’re silently testing:

Can the founder explain any number without the spreadsheet?

Do assumptions change logically when inputs shift?

Does the model expose sensitivity—or hide it?

If the founder needs the spreadsheet to speak for them, trust erodes.

Strong founders treat the model as supporting evidence, not a shield.

The difference between modeling understanding and modeling compliance

Some founders build models to look compliant:

matching expected formats

ticking investor checkboxes

mirroring other startups

Others build models to understand reality:

where growth breaks

where cash stress appears

where decisions matter most

Investors can tell which mindset is present.

Compliance models feel performative.

Understanding models feel operational.

Only one earns confidence.

Why early-stage models are about priorities, not predictions

At early stages, investors know forecasts will be wrong.

What they care about is:

what the founder chose to model

what they chose to omit

what risks they surfaced

what assumptions they treated as fragile

These choices reveal priorities.

Templates that encourage founders to model everything equally erase those signals.

That’s a loss, not a gain.

How founders should approach templates going forward

The correct framing is not:

“Does this model look professional?”

But:

“Does this model help me explain decisions clearly?”

Founders who can say:

“This assumption matters most, and here’s why”

earn more trust than those with immaculate spreadsheets.

Core takeaway for Section 5

Financial templates don’t build confidence.

Understanding does.

A simple model with clear logic beats a complex one built to impress.

Investors fund founders who know which numbers matter—and why.

This aligns closely with how investors judge traction and metrics as signals of execution quality rather than spreadsheet precision.

Section 6 — Example Decks: What to Study, What to Ignore, and How Investors Expect You to Learn From Them

Founders love example decks.

Investors are cautious about them.

This isn’t because examples are useless. It’s because most founders study examples the wrong way—and investors can tell when someone has learned the surface but missed the system underneath.

Example decks are not answers.

They are artifacts of decisions made in specific contexts.

Missing that context is where credibility quietly erodes.

Why investors don’t think in “great decks”

Founders often refer to “great decks” as if they’re universally great.

Investors don’t.

When investors remember a deck, they remember:

the market moment it fit

the risk profile it clarified

the questions it neutralized

the fund thesis it matched

A deck that worked once did so because it aligned with a very particular situation.

Studying only the slides without the situation produces false learning.

What investors actually want founders to extract from examples

When investors see a founder reference an example deck, they’re listening for how that example informed thinking.

They want to hear:

“This slide solved a trust problem at that stage.”

“This structure reduced confusion about risk.”

“This framing worked because competition was low.”

They don’t want to hear:

“This deck raised money, so we followed it.”

“This is how successful startups do it.”

The first signals understanding.

The second signals imitation.

The difference between borrowing structure and borrowing confidence

Many founders unconsciously borrow confidence, not structure.

They replicate:

bold claims

aggressive projections

assertive narratives

without owning the underlying risk.

Investors notice the mismatch fast.

Confidence without constraint reads as posture—not conviction.

Good examples teach how confidence was earned, not how it was expressed.

Why famous decks are the most dangerous teachers

Airbnb, Uber, and other famous decks are deeply misleading for early-stage founders.

Not because they’re bad—but because:

the market believed early

timing reduced risk

skepticism was lower

capital was abundant

Those decks didn’t create trust.

They rode it.

Using legendary examples without adjusting for modern investor skepticism creates unrealistic expectations—about both storytelling and traction.

How example misuse creates investor friction

Misused examples often trigger subtle resistance:

claims that feel inflated for the stage

language that assumes belief instead of earning it

analogies that shortcut explanation

Investors don’t push back directly.

They simply disengage.

Founders rarely realize the cause was borrowed certainty, not weak data.

What investors respect in founders who cite examples

Investors respond positively when founders say things like:

“We studied this example, but rejected this section.”

“This worked for them, but fails in our market.”

“We borrowed the logic, not the slides.”

This shows discrimination.

Founders who can explain why an example does not apply often sound more credible than those who overuse it.

How to study example decks productively

The right way to study examples is to ask:

what doubt was this slide addressing?

what trade-off was embedded here?

what assumption was left implicit?

what was simplified—and why?

Then discard everything visual.

What remains is the decision logic.

Rebuild from there.

Why originality matters less than intentionality

Investors don’t demand originality for its own sake.

They demand fit.

A familiar structure used intentionally outperforms a novel one used blindly.

Intentional founders:

know why something exists

know when it should be removed

know how it must evolve

Examples are only useful once you reach that mindset.

The silent test investors apply

When founders reference examples, investors quietly ask:

“If this example fails, can this founder still explain their logic?”

If the answer feels uncertain, trust drops.

If the founder’s reasoning stands on its own, examples enhance credibility instead of replacing it.

Core takeaway for Section 6

Example decks are not lessons in what to say.

They are lessons in why certain decisions worked at a specific time.

Learn the logic.

Ignore the legend.

That’s how investors expect you to use examples.

Section 7 — The Hidden Role of Tools in Investor Confidence (Why Less Often Signals More)

Founders usually think investors gain confidence from what they see.

In reality, investor confidence often comes from what isn’t shown.

The absence of unnecessary tools, metrics, and systems frequently signals more competence than their presence. This runs counter to common startup advice—but it reflects how experienced investors interpret restraint.

Why tool restraint reads as control

Investors spend their days evaluating risk.

When a founder presents a sprawling tool stack early:

dashboards

automation layers

layered reporting systems

investors don’t see sophistication.

They see complexity introduced before clarity.

Founders who deliberately keep tooling minimal signal:

direct engagement with the business

early detection of issues

faster learning cycles

Control is not about volume.

It’s about responsiveness.

How tools influence investor perception subconsciously

Investors rarely comment on tools directly.

Instead, tools shape how founders:

answer follow-up questions

navigate uncertainty

explain past decisions

Founders deeply embedded in tooling often:

defer to dashboards

struggle to narrate causal links

frame answers through outputs instead of decisions

This creates distance.

Founders who can explain outcomes without referencing systems feel closer to the reality of the business.

That proximity builds trust.

Why fewer tools improve investor signal clarity

Every additional tool adds:

latency

abstraction

interpretation distance

At early stages, clarity matters more than optimization.

Sparse tooling forces founders to:

understand core drivers

engage with raw data

notice issues before they’re normalized

Investors prefer founders who spot problems early—even if systems are crude—over founders who detect issues late through polished interfaces.

The difference between tool confidence and decision confidence

Tool confidence sounds like:

“Our dashboard shows…”

“The platform automatically calculates…”

“We rely on the system to track…”

Decision confidence sounds like:

“We measure this because it affects X.”

“We stopped tracking this after learning Y.”

“This metric changed our behavior.”

Investors back decision confidence.

Tools should narrate decisions—not replace them.

Why over-instrumentation backfires under investor scrutiny

Investors eventually drill past tools.

They ask:

who owns the decision?

what happens when inputs change?

how do you know when a metric lies?

Founders leaning heavily on tools often struggle here.

They’ve absorbed outputs, not logic.

This creates friction in meetings.

Founders with fewer tools but stronger reasoning move faster through questioning.

Tool selection as a maturity signal

Tool maturity is not about sophistication—it’s about timing.

Investors expect:

early-stage: clarity, adaptability, hands-on control

growth-stage: consistency, delegation, repeatability

Applying growth-stage tooling too early suggests founders copying playbooks instead of building understanding.

Restraint shows awareness of where the company truly is.

The quiet confidence investors respect

Experienced investors are drawn to founders who can say:

“We haven’t built a system for this yet, because we’re still learning.”

That sentence shows:

comfort with uncertainty

learning orientation

intellectual honesty

These traits predict better long-term execution than perfect dashboards ever will.

When tools actually strengthen confidence

Tools enhance confidence when they:

remove ambiguity investors care about

compress explanations without hiding risk

highlight surprises instead of smoothing them out

Function follows purpose.

Without purpose, tools become noise.

Core takeaway for Section 7

Investor confidence doesn’t scale with tool count.

It scales with clarity of thinking.

Fewer tools, used intentionally, often signal stronger leadership than sophisticated stacks deployed prematurely.

In many cases, this quietly triggers investor red flags long before explicit feedback is ever given.

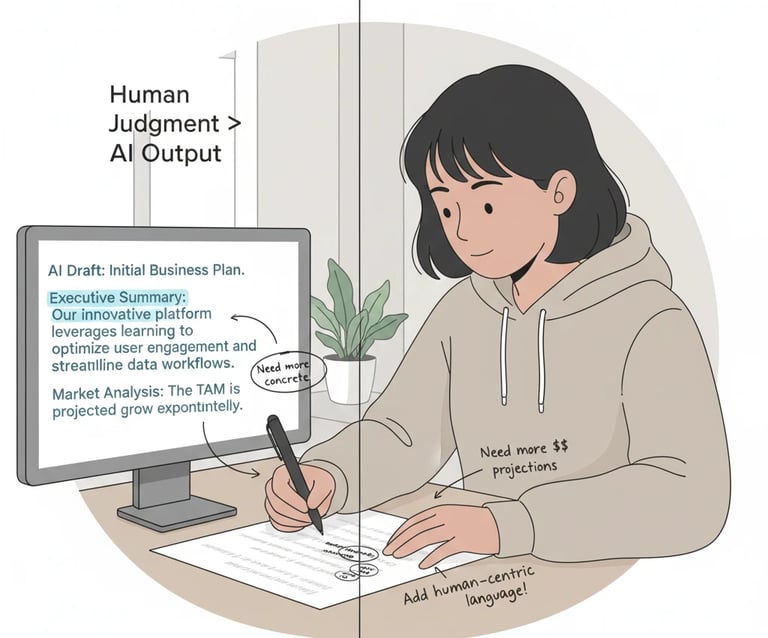

Section 8 — AI Tools in Pitching: Signal of Leverage or Quiet Liability?

AI has changed how founders build decks faster than any tool shift in the last decade.

Investors know this.

What they’re still deciding is what AI usage signals about a founder’s judgment.

AI itself is not the issue.

Unexamined reliance is.

Why investors are not anti-AI (but are alert to it)

Despite common fear, most investors are not resistant to AI-assisted work.

They use AI internally themselves:

for research summaries

pattern recognition

initial filtering

scenario brainstorming

The concern isn’t whether AI was used.

It’s whether the founder:

understands where AI helped

knows where it failed

retained ownership of decisions

AI doesn’t disqualify a founder.

It amplifies what’s already there—just like any other tool.

The real investor question AI surfaces

When investors see AI-polished language or visuals, they quietly ask:

“Is this founder thinking faster — or avoiding thinking?”

This distinction matters.

AI can:

improve articulation

compress drafts

generate alternatives

But it cannot:

select the right trade-offs

judge feasibility

calibrate ambition

decide what not to say

Founders who treat AI as an author often lose credibility.

Founders who treat AI as a collaborator usually gain it.

How investors detect AI overreach instantly

Most founders assume AI use is invisible.

It isn’t.

Investors recognize:

overly smooth but shallow phrasing

generic strategic language

confident assertions without constraint

slides that sound “right” but say little

This doesn’t trigger outrage.

It triggers doubt.

Doubt slows momentum, even when everything looks professional.

Where AI actually helps founders in pitching

Used correctly, AI is extremely valuable in specific roles:

restructuring narratives for clarity

stress-testing explanations

identifying missing sections

simplifying language after thinking is done

AI performs best after judgment has occurred.

Founders who decide first and refine with AI feel sharper — not synthetic.

Where AI creates real investor risk

AI becomes a liability when founders:

generate positioning statements without grounding

produce market narratives without lived understanding

output financial logic they can’t defend

outsource framing to prompts

Investors don’t penalize AI use.

They penalize non-ownership.

A founder who can’t explain reasoning without AI support appears fragile.

The difference between AI-assisted decks and AI-authored decks

Investors don’t object to assistance.

They object to substitution.

AI-assisted decks:

reflect founder voice

adapt under questioning

reveal thinking when challenged

AI-authored decks:

collapse under follow-ups

repeat abstract language

lose coherence off-script

The difference becomes obvious within minutes of discussion.

How AI changes the bar, not the rules

AI hasn’t lowered the standard for founders.

It has raised it.

Because producing a clean deck is easier, investors now look deeper:

sharper logic

clearer trade-offs

stronger assumptions

better judgment

When execution friction drops, judgment becomes the differentiator.

AI accelerates this shift.

How top founders talk about AI with investors

Founders who handle AI well don’t hide it.

They frame it honestly:

“We used AI to explore alternatives, then chose this.”

“AI helped compress drafts — the structure is ours.”

“We rejected the AI output here because it didn’t fit.”

This transparency signals control.

Control builds trust.

Why AI doesn’t remove the need for original thinking

AI can remix known patterns.

It cannot:

understand your market’s nuance

feel customer friction

judge investor psychology

balance ambition with plausibility

Investors back founders who can do those things.

AI can assist.

It can’t substitute.

Core takeaway for Section 8

AI is not a shortcut to conviction.

It’s a multiplier of clarity or confusion, depending on how it’s used.

Founders who treat AI as leverage look modern and capable.

Founders who treat it as authority look unprepared.

Some founders use AI pitch deck analysis to stress-test clarity and investor risk signals before ever sending a deck out.

Section 9 — Internal Tools Investors Assume You Have (Even If They Never Ask)

Most investors won’t ask you what tools you use internally.

That doesn’t mean they aren’t forming assumptions.

They infer your internal systems indirectly—through how you speak, how you answer questions, and how consistently your story holds under pressure. Often, the absence of expected internal tooling shows up long before the absence itself is discussed.

Why investors assume tooling before they see it

Investors operate on pattern recognition.

When a founder explains decisions clearly, responds consistently, and navigates questions smoothly, investors assume:

some form of internal tracking exists

decisions are documented

learning loops are active

When answers drift, change, or feel improvised, investors infer the opposite.

Tooling is not verified directly — it is deduced behaviorally.

The invisible tools investors expect early-stage founders to have

Even at early stages, investors implicitly expect:

a way to track core metrics (even if manual)

a method for documenting key decisions

a habit of reviewing performance regularly

This does NOT require:

enterprise software

advanced analytics

complex dashboards

A simple system consistently used beats an advanced system poorly understood.

Consistency signals discipline.

How lack of internal tooling reveals itself unintentionally

Founders often think missing tools can be hidden.

They can’t.

It shows up when:

metrics can’t be recalled reliably

assumptions change unintentionally

explanations contradict earlier statements

decisions seem reactionary

Investors don’t label this as “no tools.”

They label it as low operational clarity.

That perception is far more damaging.

Why investors care more about habits than platforms

Platforms come and go.

Investors care about habits:

how often founders review reality

how quickly signals are noticed

how decisions evolve over time

A founder with disciplined habits can outgrow weak tools.

A founder without habits collapses under strong ones.

Investors back the habit, not the software.

The quiet expectation of documentation

Investors assume that important decisions live somewhere:

why a pivot was made

why a metric was chosen

why a strategy changed

Not because they want to audit it — but because repeatability requires memory.

Founders who rely entirely on intuition without documentation appear less scalable.

Scalability begins with remembering why choices were made.

Why “we track it in our heads” makes investors nervous

Some founders pride themselves on mental tracking.

Investors don’t.

Mental systems:

don’t scale

don’t survive stress

don’t transfer to teams

Even lightweight documentation signals future-readiness.

Investors aren’t expecting polish.

They’re expecting intent.

How internal tooling aligns with investor trust

When internal tools exist:

answers become more grounded

consistency improves

trade-offs are clearer

This creates a subtle trust loop:

investors ask deeper questions

founders respond with clarity

conviction builds incrementally

Without visible internal scaffolding, this loop breaks early.

The difference between private tooling and public polish

Some founders confuse internal systems with presentation artifacts.

They’re not the same.

Internal tools exist to:

inform decisions

surface problems

guide prioritization

Investor-facing materials exist to:

explain reasoning

communicate direction

represent judgment

Strong founders understand the difference—and keep both clean.

Core takeaway for Section 9

Investors don’t need to see your internal tools.

But they can feel when they’re missing.

Consistency, recall, and clarity reveal more than any dashboard ever will.

Build internal systems for understanding, not display.

Investors will notice—without asking.

A comprehensive VC pitch deck guide often reveals which internal processes investors assume founders already have in place.

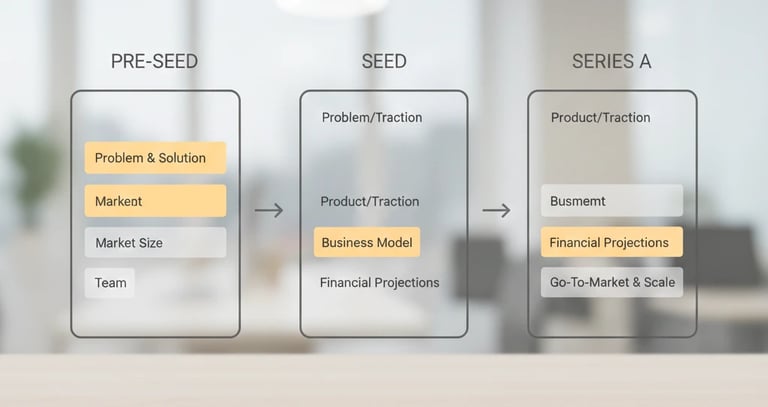

Section 10 — Templates Across Stages: Why What Works at Pre-Seed Breaks at Series A (and Vice Versa)

One of the fastest ways founders lose investor trust is by using the wrong templates at the wrong stage.

Investors don’t judge decks in isolation.

They judge them relative to where the company should be.

A deck that feels “too advanced” can look just as risky as one that feels underdeveloped.

Why investors mentally recalibrate templates by stage

Every funding stage has a different job to do.

Investors subconsciously ask:

What uncertainty should already be resolved?

What uncertainty is still acceptable?

What decisions must this founder now prove they can handle?

Templates are only useful when they reinforce the right questions for the stage.

Misalignment here signals poor fundraising judgment.

Pre-Seed: Templates should reveal thinking, not outcomes

At pre-seed, investors expect:

ambiguity

incomplete data

evolving strategy

What they are evaluating is how founders reason in uncertainty.

Templates work at this stage only if they:

prioritize problem clarity

explain why a direction was chosen

surface risks explicitly

keep numbers directional, not exact

Overly detailed templates at pre-seed backfire.

They suggest the founder is manufacturing certainty instead of learning.

Seed stage: Structure matters more than polish

At seed, investors look for:

early validation

emerging repeatability

clearer go-to-market logic

Templates now serve a different role:

connecting traction to strategy

showing learning velocity

demonstrating prioritization

The biggest mistake founders make here is reusing their pre-seed deck with more slides.

What investors want instead is evolution:

clearer assumptions

sharper metrics

cleaner narrative trade-offs

A seed deck should feel tighter — not just longer.

Series A: Templates must signal operational maturity

By Series A, templates are no longer optional scaffolding.

They become expectation baselines.

Investors now care about:

unit economics logic

repeatable growth engines

internal alignment

forward-looking risk management

Templates that still over-index on vision without operational grounding feel immature at this stage.

Conversely, over-complex decks that bury the narrative under metrics feel unleadable.

Balance is the test.

Why “one deck for all stages” fails silently

Some founders try to design a universal deck.

Investors immediately sense this.

Universal decks:

blur priorities

dilute signal

confuse stage-specific expectations

A deck that tries to satisfy every stage convinces no stage.

Investors want to see that founders understand who they’re talking to now.

How investors read evolution between rounds

Investors compare your current deck to your past one—even if they never say it.

They’re looking for:

what assumptions disappeared

what new risks emerged

what confidence was earned, not assumed

Templates that don’t visibly evolve suggest stagnation.

Evolution signals learning.

Learning signals competence.

The stage-specific template trap founders fall into

Founders often ask:

“What does a Series A deck look like?”

This is the wrong question.

The right one is:

“What must be true for a Series A investor to believe us?”

Templates don’t create truth.

They communicate it.

Investors reject decks that look right but don’t align with underlying readiness.

How sophisticated founders use stage templates

Strong founders:

choose templates that enforce stage discipline

remove sections that no longer matter

expand sections that now carry risk

let structure reflect company maturity

This adaptability reads as leadership.

Rigidity reads as inexperience.

Core takeaway for Section 10

Templates are not universal tools.

They are stage-calibrated lenses.

When your deck structure aligns with the investor’s expectations for that stage, trust accelerates.

When it doesn’t, skepticism forms quietly—and early.

Section 11 — How Founders Misuse Examples to Justify Weak Thinking (and Why Investors Notice)

Examples are meant to sharpen judgment.

Many founders use them to avoid making one.

This is one of the most common — and least discussed — reasons investors quietly disengage. The deck looks thoughtful. The logic sounds familiar. But at the core, decisions are borrowed, not earned.

Investors don’t object to learning from others.

They object to founders outsourcing conviction.

Why examples feel safer than original decisions

Examples offer psychological comfort.

They allow founders to say:

“Others did this before us.”

“This approach has worked already.”

“We’re following best practices.”

The problem is that investors are not funding precedents.

They’re funding judgment under uncertainty.

Examples reduce emotional risk for founders, but they do not reduce investment risk.

The most common justification pattern investors recognize

Investors hear variations of this constantly:

“We structured it this way because [successful company] did.”

This reveals two issues:

the founder is appealing to authority

the founder is avoiding defending the decision independently

Investors immediately wonder what happens when:

conditions change

the analogy breaks

reality diverges

Founders who can’t stand behind their own reasoning feel fragile.

Why investors distrust example-backed certainty

Certainty that comes from examples feels different than certainty that comes from understanding.

Example-backed certainty:

collapses under probing

relies on analogy over evidence

struggles to adapt

Understanding-backed certainty:

survives questioning

explains trade-offs calmly

evolves without defensiveness

Investors are sensitive to this distinction because it predicts future decision quality.

How examples become rhetorical shields

Some founders use examples not as learning aids, but as shields.

They deploy:

“This is how X did it”

“Top startups follow this model”

“This is industry standard”

These phrases shut down inquiry — intentionally or not.

Investors see this as avoidance, not strength.

They don’t want consensus.

They want accountability.

Why borrowed logic fails under investor pressure

During deep discussions, investors test:

first-principles understanding

adaptability

causal logic

Borrowed logic cannot be defended without the original context.

When that context breaks, founders stumble.

Investors don’t penalize being wrong.

They penalize not knowing why you believed something.

The survivorship bias problem founders underestimate

Founders often study decks from companies that succeeded.

Investors remember the many similar decks that failed.

When a founder justifies choices using winners alone, investors worry that:

downside scenarios weren’t considered

alternatives weren’t explored

luck is being mistaken for strategy

That worry lingers long after the meeting.

What investors respect instead of example mimicry

Investors lean forward when founders say:

“We considered this approach but rejected it because…”

“We tested this assumption and it failed here…”

“This works in X context, but not in ours…”

These statements show ownership.

Ownership breeds trust.

Even imperfect decisions earn respect when they’re reasoned and examined.

How to reference examples without losing credibility

Examples strengthen credibility only when they:

support logic you already believe

illustrate trade-offs you’ve articulated

validate thinking, not replace it

If an example disappears, your reasoning should still stand.

That’s the bar investors apply.

Core takeaway for Section 11

Examples should inform judgment, not excuse its absence.

Founders who hide behind precedents slow investor conviction.

Founders who stand behind their own reasoning — even imperfect reasoning — move investors forward.

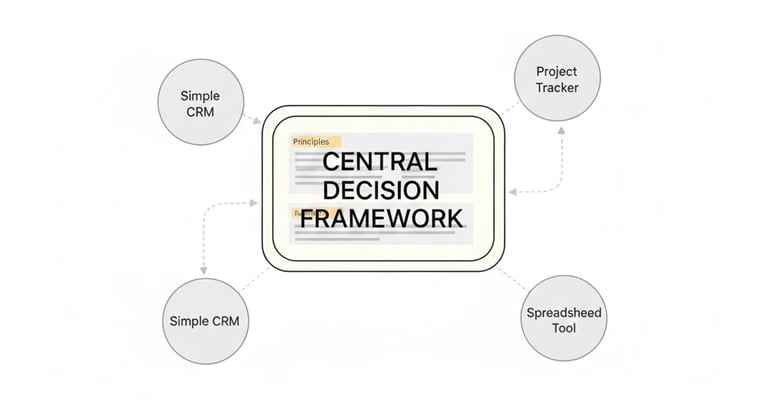

Section 12 — Building Your Own Internal Playbook (Why Systems Beat Stacks Every Time)

Founders who rely on tools often end up managing outputs.

Founders who build playbooks manage decisions.

Investors know the difference.

A tool stack can look impressive.

An internal playbook feels inevitable.

This section is about why experienced founders stop chasing tools—and start designing how decisions are made, revisited, and evolved.

Why investors value internal playbooks more than external tools

An internal playbook answers questions tools never will:

How do we decide what matters this quarter?

How do we recognize when assumptions break?

How do we revise strategy without losing direction?

Investors don’t expect perfection here.

They expect deliberateness.

When founders operate from a playbook, investors sense coherence—even when execution is still rough.

What an internal playbook actually is (and isn’t)

An internal playbook is not:

a software system

a deck

a set of documents

It is a shared mental model for:

prioritization

decision ownership

learning loops

Tools may support it—but they don’t define it.

Founders with a playbook can change tools freely without confusion.

Founders without one become stuck adapting their thinking to software.

How playbooks emerge naturally in strong teams

Strong playbooks aren’t written all at once.

They emerge from:

repeated decisions

post-mortems

visible trade-offs

documented reasoning

Over time, patterns form:

what metrics matter most

when bold bets are acceptable

when to slow down

Founders who capture these patterns build operational memory.

Investors value that memory more than any dashboard.

Why chasing tools delays real system-building

Early on, founders often mistake activity for progress.

They adopt tools to:

feel organized

reduce ambiguity

signal professionalism

But without a playbook, tools often:

create false stability

encourage reactive behavior

obscure root causes

Founders who solve every problem with a new tool never learn which problems actually matter.

Investors notice the drift.

What investors listen for when assessing internal systems

Investors evaluate internal playbooks indirectly by listening for:

consistency of decision logic

clarity in trade-offs

repeatable reasoning across topics

When founders explain different areas of the business using the same mental framework, investors infer a playbook exists—even if it’s informal.

That inference builds confidence.

Why playbooks scale better than tools

Tools scale usage.

Playbooks scale judgment.

As teams grow:

tools fragment across roles

dashboards multiply

abstraction increases

A shared playbook keeps everyone aligned despite tool sprawl.

Investors know companies break not from lack of software—but from divergence in reasoning.

Playbooks prevent that early.

How playbooks show up in investor conversations

Founders with internal playbooks:

answer questions consistently

acknowledge uncertainty calmly

explain trade-offs without defensiveness

Their answers feel related, not isolated.

This coherence signals leadership maturity—even at early stages.

Founders without playbooks feel episodic.

Each answer stands alone.

Investors subconsciously trust continuity more than competence.

Designing your playbook before choosing tools

The correct order is:

Decide how you make decisions

Identify what needs to be visible

Choose tools that support that visibility

Most founders reverse this.

Investors silently discount founders who lead with tools before logic.

The order matters.

Core takeaway for Section 12

Great founders don’t build stacks.

They build systems for thinking.

Tools come and go.

Playbooks endure.

And investors back founders whose logic remains intact—even as everything else changes.

Section 13 — Tools as Communication, Not Configuration (Why Readability Beats Sophistication)

Most founders treat tools as configuration engines.

Investors experience them as communication layers.

This gap explains why highly technical, meticulously configured decks often perform worse than simpler ones. The tool may be powerful—but if it communicates poorly, investor trust drops.

Clarity, not capability, is what closes the gap.

Why investors don’t reward sophisticated configuration

Founders often optimize tools for internal correctness:

detailed settings

layered logic

complex visual systems

Investors are not evaluating internal mastery in a pitch.

They are evaluating:

speed of comprehension

ease of navigation

clarity of cause-and-effect

A configuration-heavy artifact slows all three.

When investors work harder to understand your thinking, they subconsciously discount the outcome.

How readability became the investor’s primary metric

Investors review hundreds of decks.

They are not short on intelligence.

They are short on attention.

Anything that forces them to:

decode layouts

interpret symbols

infer relationships

toggle between references

creates friction.

Friction weakens conviction—even if content is accurate.

Readability accelerates belief.

Why clean communication signals leadership maturity

Clear communication signals:

respect for audience time

command of material

confidence in priorities

Complex communication signals:

uncertainty

fear of omission

desire to impress

Investors bet on founders who can distill complexity, not display it.

This is why minimal decks often outperform sophisticated ones in early meetings.

The mistake of “showing the system”

Many founders want to show how much work went into building the system.

Investors don’t want to see the system.

They want to see:

what the system concluded

why that conclusion matters

what decision follows

Systems that demand explanation distract from judgment.

The more a tool has to explain itself, the less useful it becomes in a pitch context.

How investors interpret over-engineered communication

Over-engineered decks subtly suggest:

indecision masked as completeness

insecurity disguised as detail

lack of prioritization

Investors don’t criticize this openly.

They simply feel:

“This is harder than it needs to be.”

And move on.

Communication compression as a skill investors value

The strongest founders can:

collapse complex models into simple narratives

explain outcomes without reopening tools

move fluidly between numbers and meaning

Tools help produce these insights—but don’t replace the founder’s ability to communicate them.

That ability is what investors assess.

Why configuration-heavy decks struggle under questioning

When investors ask follow-ups:

configuration-heavy founders reopen tools

communication-driven founders explain logic

The second group moves faster.

Speed under questioning builds confidence.

It suggests preparedness beyond slides.

Tools should disappear in the conversation

The best investor conversations reach a point where:

the deck fades away

the tool becomes irrelevant

the founder speaks directly

If the tools cannot disappear, they’ve taken on too much work.

Founders should be able to leave tools behind without losing coherence.

Core takeaway for Section 13

Tools don’t impress investors by being powerful.

They impress investors by being invisible.

When communication is clean, credible, and compressed, tools have done their job.

When tools demand attention, trust leaks.

Section — 14 When Not to Use Tools, Templates, or Examples (Why Simplicity Often Wins Meetings)

There are moments in fundraising where adding tools, templates, or examples actively damages your position.

Most founders miss this because they assume more preparation always equals more confidence. Investors don’t see it that way. They’re often most impressed when founders know what not to use.

Restraint, at the right time, is a signal of judgment.

Why investors distrust over-engineering early conversations

Early-stage investor meetings are not technical audits.

They are sense-making conversations.

When founders arrive with:

deeply layered frameworks

heavy tooling explanations

dense example references

investors feel boxed into the founder’s system rather than guided through their thinking.

This creates resistance.

Investors want to explore possibility, not navigate infrastructure.

The danger of tools before alignment

Tools introduce structure.

Structure makes assumptions explicit.

If alignment hasn’t been earned yet, explicit structure can backfire.

Common failure modes:

metrics before belief

forecasts before narrative alignment

frameworks before curiosity

Investors need to understand why they should care before seeing how everything works.

Strong founders stage the reveal.

Why minimal decks often outperform polished systems

Some of the strongest investor meetings begin with:

fewer slides

lighter structure

conversational pacing

This isn’t laziness.

It’s strategic.

Minimal artifacts:

invite questions

surface objections earlier

let investors co-shape the discussion

Co-creation builds buy-in.

Over-definition shuts it down.

When templates actively suppress founder voice

Templates tend to standardize language.

That’s useful—until it mutes conviction.

Investors quickly disengage when:

slides sound interchangeable

phrasing feels pre-approved

claims lack personal grounding

Founders who step away from templates at key moments often sound more believable, not less professional.

Voice matters more than uniformity.

Why examples can limit imagination

Examples anchor expectations.

That’s dangerous when fundraising requires vision expansion.

If investors stay mentally tied to:

past category definitions

familiar playbooks

known outcomes

they may never explore upside you’re uniquely positioned to unlock.

Early conversations sometimes require unanchored thinking.

Examples can prematurely collapse possibility.

The meetings where tools should disappear entirely

There are moments founders should abandon tools altogether:

first conversations with new funds

exploratory partner chats

follow-ups focused on intuition and fit

In these moments, investors watch:

how founders reason live

how they absorb feedback

how thinking evolves

Tools slow this process.

Presence speeds it up.

Simplicity as a proxy for conviction

Investors often equate simplicity with:

clarity of belief

command over uncertainty

confidence in direction

Complication feels like hedging.

Founders who can say less—and have it land—feel more fundable than those who say everything.

Knowing when to reintroduce structure

This isn’t an argument against tools forever.

It’s about timing.

As conviction builds, tools become supportive again:

models deepen alignment

templates enforce discipline

examples calibrate expectations

Strong founders modulate structure across conversations.

They don’t deploy everything at once.

Core takeaway for Section 14

Tools, templates, and examples are not inherently helpful.

Their value depends on timing and intent.

Founders who know when to simplify—and when to step back entirely—create more space for belief to form.

That space often closes the meeting.`

Section 15 — Synthesis: How Strong Founders Use Tools Without Losing Credibility

Everything in this pillar converges on a single truth investors learn through experience:

Tools don’t create certainty.

Judgment does.

Templates, examples, AI systems, and frameworks only matter insofar as they support judgment — never when they attempt to replace it.

This final section ties together what investors actually internalize when they evaluate how founders use tools.

How investors mentally combine all the signals

Investors don’t score tools individually.

They synthesize:

how founders chose them

when founders relied on them

where founders ignored them

whether founders could reason without them

From this, investors form a single conclusion:

“Does this founder think independently under uncertainty?”

Strong founders answer “yes” without announcing it.

Weak ones unintentionally answer “no” through over-reliance.

What mature tool usage looks like in practice

Mature founders display consistent patterns:

tools clarify, they don’t dominate

templates guide flow, not conclusions

examples inform thinking, not authority

AI accelerates drafts, not decisions

Across conversations, their logic remains intact even if the materials disappear.

That continuity is what investors trust.

Why judgment becomes increasingly visible as tools improve

Ironically, better tools make weak judgment more obvious.

As execution barriers fall:

polish becomes cheap

structure becomes replicable

aesthetics stop differentiating

What remains is:

how founders prioritize

how they assess risk

how they explain trade-offs

how they respond when assumptions crack

Tools raise the bar by removing excuses.

How strong founders avoid the “tool identity trap”

Some founders unconsciously define themselves by their stack:

“we built this with X”

“we rely heavily on Y”

“our process is driven by Z”

Strong founders define themselves by decisions:

“we chose this trade-off”

“we rejected this path”

“we stopped tracking that metric”

Identity rooted in decisions feels durable.

Identity rooted in tools feels fragile.

Investors sense the difference immediately.

The investor’s real takeaway from tool discipline

By the end of a meeting, investors rarely remember:

which software you used

which template you followed

which example you cited

They remember:

whether your thinking held together

whether your confidence felt earned

whether your logic adapted under pressure

Tool discipline quietly shapes all three outcomes.

What founders must internalize going forward

Founders who win internalize a simple hierarchy:

Judgment comes first

Tools follow judgment

Templates serve structure

Examples sharpen reasoning

Everything remains discardable

Tools are leverage — never authority.

The moment founders grant tools authority, they surrender credibility.

How this pillar connects back to the full system

Pillar 12 completes the loop formed by the earlier pillars:

strategy without structure is vague

structure without psychology is brittle

psychology without judgment collapses under pressure

Tools sit at the bottom of this stack.

They amplify what’s already there.

If judgment is strong, tools become invisible.

If judgment is weak, tools make that weakness louder.

Final insight before moving forward

Investors don’t fund decks.

They don’t fund templates.

They don’t fund tools.

They fund decision-makers.

Everything in this pillar exists to help founders become one — visibly, consistently, and under scrutiny.

Frequently Asked Questions — Tools, Templates & Examples

1. Do investors dislike pitch deck templates?

No. Investors don’t dislike templates — they dislike unexamined use of them. When founders rely on templates without understanding why each section exists or how it applies to their business, confidence drops. Templates are respected when they support thinking, not when they replace it.

2. Is it okay to use successful startup pitch deck examples?

Yes, but only as learning references, not blueprints. Investors expect founders to extract logic and decision-making patterns, not to copy structure or language. Borrowing confidence from examples without context weakens credibility.

3. Can AI-generated pitch decks hurt fundraising chances?

AI alone does not hurt credibility. Over-reliance does. Investors quickly recognize when polish outpaces substance. AI is valuable for refining clarity after thinking is complete, not for generating conviction. Founders must still own every decision.

4. What tools do investors expect early-stage founders to use?

Investors expect some form of tracking, documentation, and consistency, even if it’s simple or manual. They care more about habits and discipline than software sophistication. Consistency signals maturity.

5. Should early-stage founders use financial model templates?

They can, but cautiously. Financial templates help structure thinking, yet often backfire when founders accept default assumptions or force false precision. Investors read models for logic and sensitivity, not mathematical perfection.

6. How many tools is “too many” for a startup?

There’s no fixed number, but investors become skeptical when tools begin to obscure clarity or slow explanations. If a founder can’t explain decisions without referencing dashboards or platforms, the tool stack is likely too heavy.

7. Should founders talk about which tools they use during pitches?

Only when directly relevant. Investors rarely care about tool names; they care about what decisions those tools enable. Leading with tools instead of reasoning often weakens the narrative.

8. What is the biggest mistake founders make with templates?

Treating templates as answers instead of scaffolding. Investors notice when founders fill every section evenly without prioritizing risk, trade-offs, or stage relevance. Strong founders customize or discard sections intentionally.

9. When are tools better left out of investor meetings?

During early or exploratory conversations. Heavy tooling can suppress curiosity and limit dialogue. Simpler materials often perform better until alignment and belief are established.

10. Do polished decks outperform simpler ones?

Not consistently. Clean communication outperforms polish, especially in early-stage fundraising. Investors value clarity of reasoning, adaptability, and confidence under questioning more than visual complexity.

11. How do investors judge tool usage without seeing the tools?

Through behavioral signals — consistency of answers, recall of metrics, clarity of logic, and composure under pressure. Strong internal systems are felt through thinking, not displayed through software.

Final Thought for Founders

By this point, one thing should be clear.

Strong fundraising isn’t about collecting the right tools.

It’s about developing the judgment to use — or ignore — them at the right moment.

Investors don’t fund polish.

They fund founders who can think clearly under uncertainty.

If you want to apply this without trial-and-error

Most founders don’t fail because they lack tools.

They fail because they assemble decks, models, and narratives without a unified system behind them.

If you want a structured way to:

apply investor-grade judgment across every slide

use templates without sounding templated

build decks that hold up under real VC scrutiny

align your pitch, story, and numbers into one coherent system

…there is a method to do that — without hiring a $5K pitch consultant.

What the system actually gives you

Not more files.

Not random templates.

But a decision-backed framework that helps you:

know what investors care about at each stage

structure your thinking before you structure slides

communicate conviction without over-explaining

avoid common signal-killing mistakes founders don’t notice

Used correctly, it compresses months of guesswork into a repeatable process.

What matters more than anything

Whether you move fast or slow — the only real advantage is clarity.

If your goal is to walk into investor conversations knowing:

why each slide exists

what questions it’s meant to answer

and how to defend every choice calmly

then having a proven system removes unnecessary uncertainty.

No pressure.

No urgency.

Just a cleaner way to build something investors can believe in.

Internal Link Hub — Related VC Pitch Deck Foundations

If you want to go deeper, these core pillars expand on the strategic, psychological, and structural foundations that shape how tools and templates should be used in fundraising:

→ Pillar 1: How VC Pitch Decks Work

Understand how investors actually read, filter, and evaluate pitch decks inside VC firms — before tools ever matter.

→ Pillar 2: Problem & Solution Slides

Learn how investors judge whether your problem framing and solution clarity justify further attention, even in early review stages.

→ Pillar 3: Slide Structure & Frameworks

Dive into the logic behind strong deck structures and why frameworks work only when adapted with judgment.

→ Pillar 4: Investor Psychology

Explore the cognitive shortcuts, biases, and decision patterns that influence how investors respond to decks, numbers, and narratives.

→ Pillar 5: Storytelling & Narrative

See how story coherence and strategic narrative outperform surface-level polish when investors form conviction.

→ Pillar 6: Design Principles

Learn why design is about readability and trust signaling — not aesthetics — and how poor design choices quietly damage credibility.

→ Pillar 7: Traction & Metrics

Understand which metrics investors actually trust, how they interpret traction signals, and why some numbers create doubt instead of confidence.

→ Pillar 8: Market Size & Competition

Learn how investors judge market realism, competitive positioning, and category logic beyond headline TAM numbers.

→ Pillar 9: Fundraising Strategy

Understand how decks fit into the broader fundraising process, investor targeting, timing, and momentum building.

→ Pillar 10: Pitch Delivery

See how delivery, presence, and explanation quality influence investor belief — even with the same slides.

→ Pillar 11: Mistakes, Red Flags & Investor Judgment

Identify subtle mistakes and credibility leaks that cause investors to disengage long before they give explicit feedback.

Why this matters

Each of these pillars reinforces a single truth:

Tools only work when judgment, structure, psychology, and strategy are already aligned.

Pillar 12 completes that system by showing how to apply everything above without losing credibility.

Funding Blueprint

© 2025 Funding Blueprint. All Rights Reserved.